Dr. Chevalier Q. Jackson

1865-1958

Physician and laryngology specialist Chevalier Jackson spent his medical career in Pennsylvania but achieved national renown. He pioneered procedures of esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy, developing ways to remove swallowed objects from the esophagus and upper airway.

In November 1865, seven months after the end of the Civil War, Chevalier Quixote Jackson was born in his parents’ house on Fourth Avenue in downtown Pittsburgh, next door to the livery stable run by his father, William Stanford Jackson.

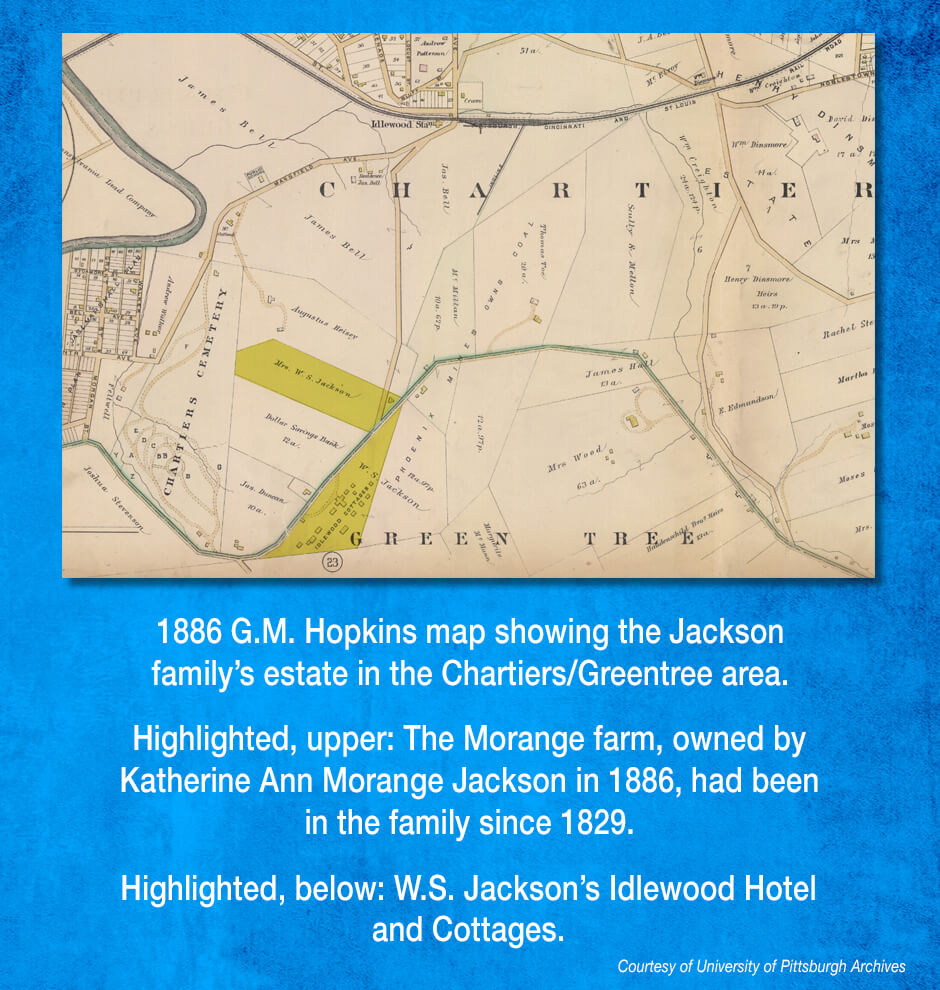

A man of considerable learning, William S. Jackson had a diploma in veterinary medicine and was an astute businessman. In 1871, he moved his family to Idlewood, which at the time was farm country several miles west of Pittsburgh, an area straddling Chartiers and Greentree. Alongside the farms were the Idlewood Mines of the Pittsburgh Coal Company.

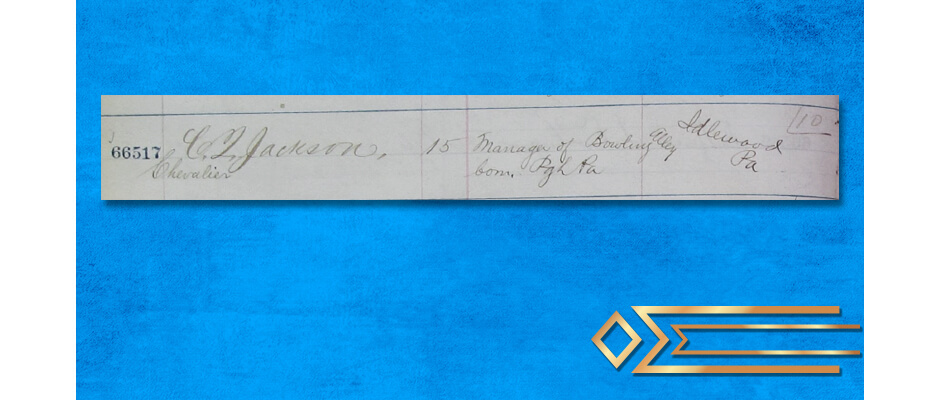

William S. Jackson opened a business on Wood Street with Alexander Frew under the name Jackson & Frew, makers of harnesses, saddles and trunks. By 1880, he had expanded his business dealings into proprietorship of the Idlewood Hotel and Cottages, a summer resort surrounded by local farms and accessible by rail from the Idlewood Station.

The second of three sons, Chevalier Jackson grew up speaking both French and English. His French heritage came from his mother, Katherine Ann Morange, whose father, John Morange, had immigrated from France in 1819 and become a farmer in Chartiers a decade later. Morange Road in Pittsburgh’s West End is named after this pioneer family.

Chevalier Jackson’s parents had a large library of books with which they supplemented their sons’ educations. Jackson thrived as a student, but his interests were not solely in scholarly pursuits. He developed advanced mechanical aptitude working with his grandfather, a skilled craftsman, in the family’s workshop, designing and sketching practical items such as picture frames, clock cases and wall brackets. While still a youth, Chevalier Jackson created a harpoon to retrieve tools lost by a wildcatter at the bottom of an exploratory oil well, as well as a sled to aid in getting to school in the winter. With his grandfather and brothers, he constructed a cottage on the family estate, which became the family home in subsequent years.

The precocious talents of the Jackson boys emerged in this environment of intense education and invention. W.S. Jackson’s summer cottages drew merchants, manufacturers and their families. The Idelwood Hotel and Cottages became a place where guests spent the summer months pursuing art, nature studies and outdoor recreation. Chevalier Jackson learned to swim in Chartiers Creek. In between chores, he enrolled in art classes and drew alongside A. Bryan Wall, son of acclaimed Pittsburgh artist Alfred S. Wall.

Chevalier Jackson and his brother Shirls B. Jackson would both become physicians, while brother Morange Stanford Jackson ran the Idlewood Hotel.

At the age of 13, Chevalier Jackson passed an entrance exam and was admitted to the Western University of Pennsylvania, now the University of Pittsburgh. He did his homework during his train commute to and from the city. At university, his interests were in physiology, geography, Latin, Greek, English and math.

Realizing that his ambitions to go to medical school were hampered by limited funds, Jackson put his artistic skills to use and got a part-time job as a glass and china decorator with the Julius A. Burgun Company. It was an in-demand talent that paid well. By 1884, Jackson had earned sufficient money to enroll in Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He graduated with a medical degree in April 1886, at the age of twenty.

Dr. Jackson set up practice in Pittsburgh, where he was eventually joined by his younger brother, Shirls, after the latter graduated from medical school. As Chevalier Jackson developed his specialty in laryngology, he also became active in public health issues, drawing attention to sanitary conditions of food and water being consumed by city residents.

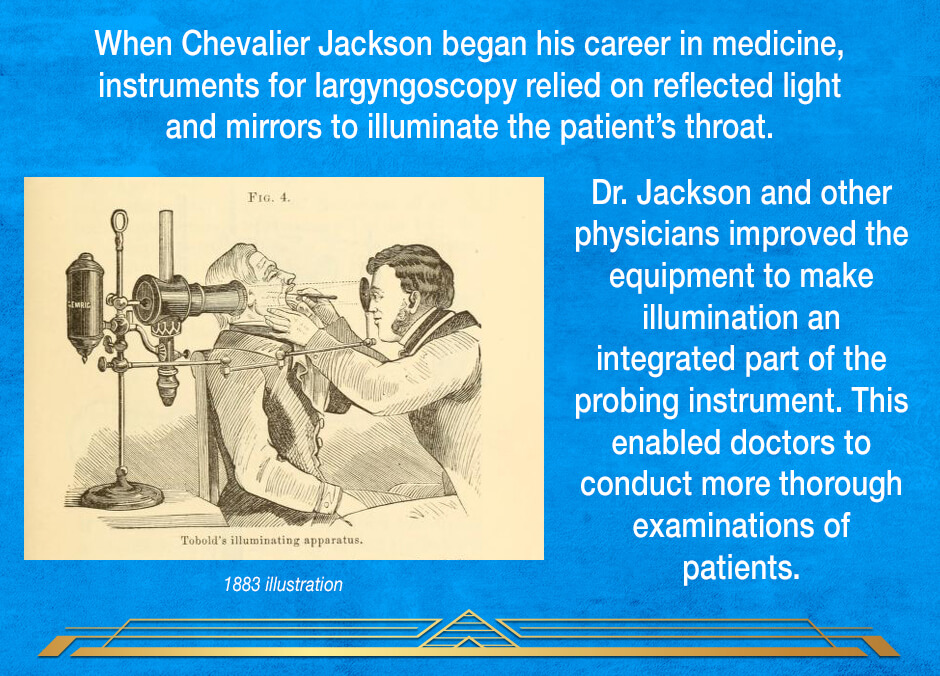

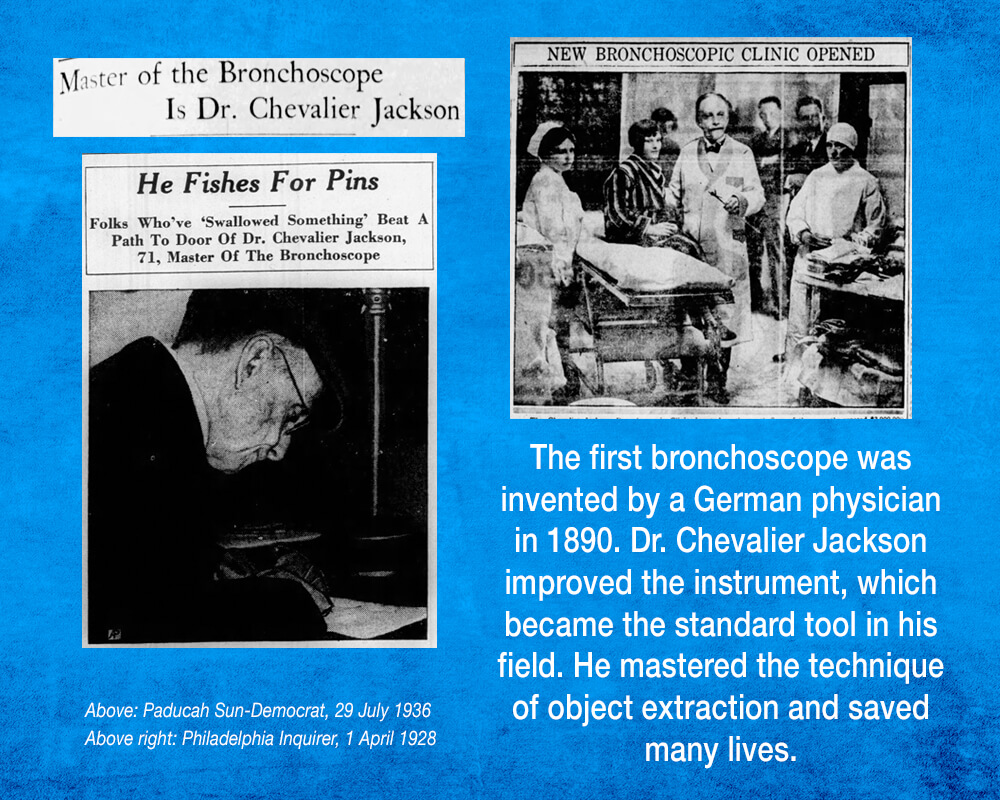

Eager to study under a specialist in his field, Dr. Jackson traveled to England and worked with Sir Morrel Mackenzie in London. Convinced that the tools used for endoscopy needed to be improved upon, Jackson set about that task when he returned to Pittsburgh. In 1890, he devised and built an esophagoscope. Over the next several decades, he continued to refine and improve the tools of his medical field with improved illumination, suction and angling. His laryngoscope, based upon Kirstein’s autoscope but improved with a tungsten light bulb, became a standard piece of equipment in the profession.

While his contributions to the development of instruments used in broncho-esophagoscopy were undeniably important, and his expertise in endoscopic techniques drew fellow physicians to consult with and learn from him, what put Dr. Jackson’s name in the newspapers was his unusual but critical sub-specialty – removing swallowed or inhaled objects from human airways and digestive tracts.

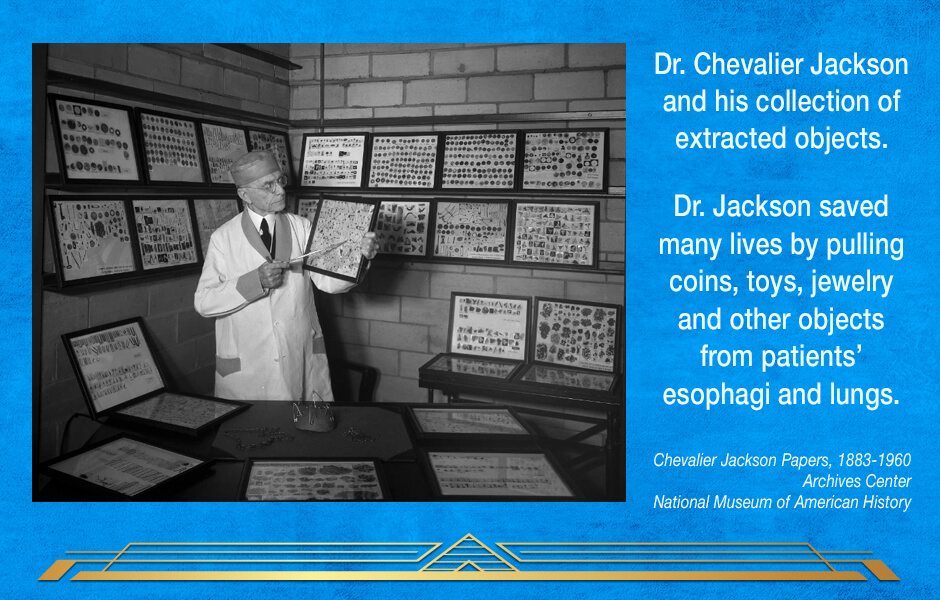

Unsurprisingly, children and youths under 15 constituted four-fifths of Dr. Jackson’s mishap-prone and unwisely curious patients. A meticulous records-keeper, Jackson not only saved the swallowed and inhaled objects he extracted from patients of all ages, but he also photographed, indexed and catalogued them. Over his career, he collected nearly 2,400 such items – pins, buttons, coins, toys, dentures, jewelry, several dentists’ drills, miniature binoculars, and at least one bullet and a padlock. His collection is on exhibit at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

Dr. Jackson’s accomplishments caught the attention of the Philadelphia medical community. In 1916, he accepted the position of chair of laryngology at his alma mater, Jefferson Medical College. The institution’s board of trustees gave Dr. Jackson their highest recommendation in their announcement of the appointment: “In his particular department Professor Jackson is the most distinguished Jefferson alumnus; no American in his specialty has done better work or has received higher recognition at home or abroad.”

As an educator, Dr. Jackson was as successful as he was a man of medicine. He became famous among his students for his “chalk talks,” lectures he gave during which he drew illustrated sketches in chalk and pastels as he spoke. His ambidexterity (learned at his grandfather’s side in the family’s workshop) and artistic skill brought to life for his students the insides of the human body.

In 1920, Dr. Jackson was named chair of bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy at the University of Pennsylvania. He was recognized as “America’s leading expert in the removal of foreign bodies from the lungs and air and food passages.” The appointment was done in cooperation with Jefferson Medical College, where Dr. Jackson remained chair of laryngology, a post he held until 1930.

By the time he assumed his new position at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Jackson’s leadership in developing modern tools and surgical techniques for the removal of foreign bodies lodged in the bronchial tubes, had helped revolutionize the treatment of these cases. Mortality was reduced from 85 percent to 2 percent. Dr. Jackson personally saved the lives of many patients, a great number of them children and infants.

Dr. Jackson’s zeal for improving public safety was something he did not leave behind in the early years of his medical career. Instead, he fought a 17-year campaign to have “poison” labels put on caustic household products such as lye. His advocacy, taken up by the American Medical Association, culminated in a victory in 1927 when the United States Congress passed a bill requiring the poison label. After President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill into law, the president sent the pen to Dr. Jackson as a token of appreciation for the physician’s public service.