The St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936

The St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936

The worst flood in Pittsburgh history occurred in March 1936 when melting snow, combined with 48 hours of steady rain, sent the rivers and streams of the Allegheny Watershed overflowing their banks.

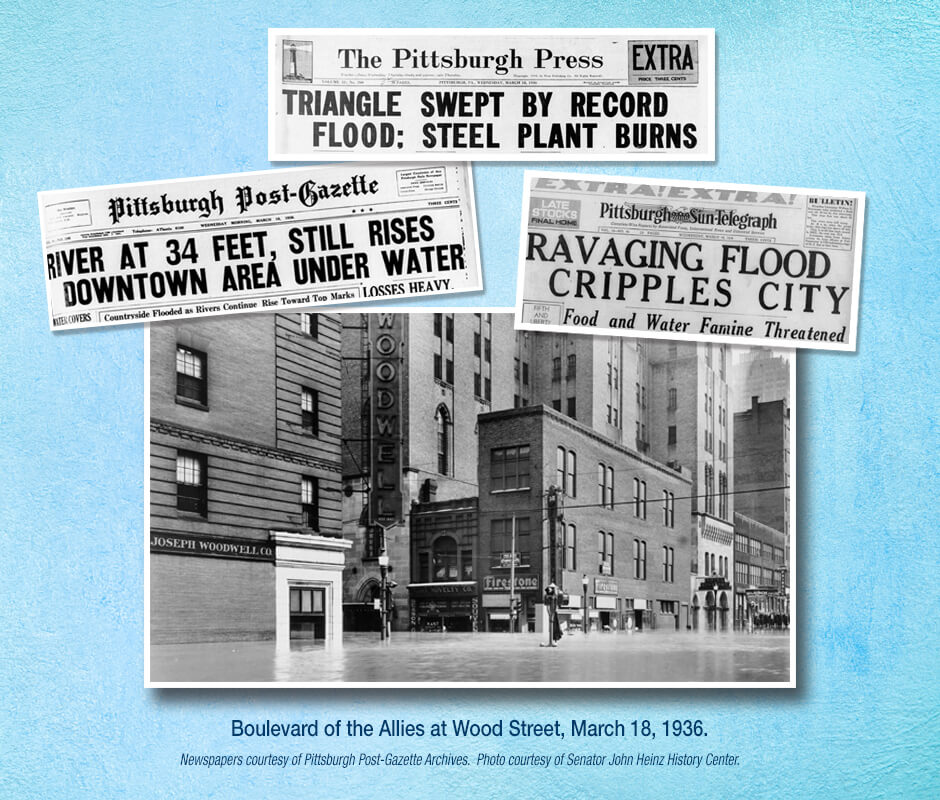

River stages at the Point exceeded flood level (25 feet) between 8:00 and 9:00 AM on St. Patrick's Day. Predictions that the water would crest at 33 feet, however, proved woefully inadequate. The high water mark, reached at 9:00 PM on Wednesday, March 18, was actually 46 feet.

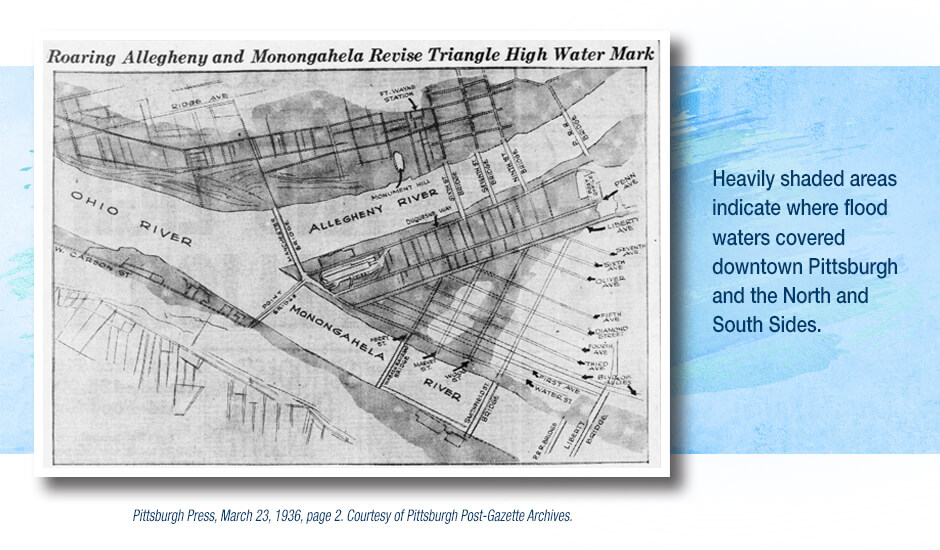

The Golden Triangle was inundated. The Jenkins Arcade, Horne's Department Store and the Roosevelt Hotel were flooded up to their second stories. Water lapped the pavement of Tenth Street on the Allegheny River side of downtown and Wood Street on the Monongahela River side. Trolley cars on Penn Avenue disappeared up to their rooflines.

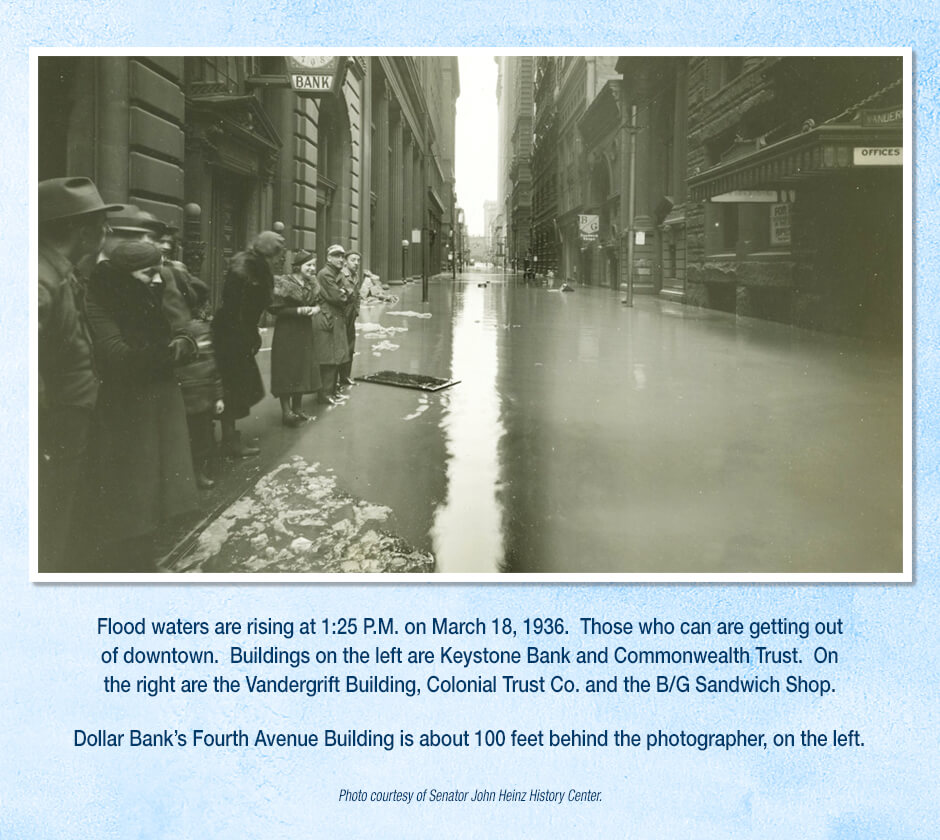

Buildings in downtown Pittsburgh lost elevator service, followed by the failure of heating, electrical and telephone services. By the afternoon of March 18th, water was rising at the rate of one foot per hour. Thousands of downtown workers evacuated the Golden Triangle and attempted to make their way home as best they could. Thousands more were trapped in the upper floors of downtown skyscrapers.

Troops from the Pennsylvania National Guard arrived in the Golden Triangle and assisted City of Pittsburgh police in establishing a picket line to protect downtown businesses from looters. No one got below Wood Street without a police pass.

The damage from the flood was severe -- $250 million in property loss throughout the Pittsburgh district. Tens of thousands of Pittsburghers were forced out of their homes, and 50,000 swelled Red Cross shelters in libraries and school gymnasiums. More than 60,000 steelworkers were put out of work until flooded mills were returned to operational status.

Recovery took time, but the city rebounded, thanks to the combined efforts of many -- police, firefighters, public works and power company employees, Red Cross volunteers, WPA workers, Boy Scouts, National Guardsmen, newspaper reporters and countless ordinary citizens.

How the Flood Affected Banks in Downtown Pittsburgh

The Pittsburgh Stock Exchange, which in 1936 was headquartered at 229-233 Fourth Avenue, next door to the Benedum-Trees Building, suspended trading operations at 10:40 AM on Wednesday, March 18, due to flooding.

By 11:00 AM, water was waist high on Market Street.

Most banks located from Wood Street to the Point were forced to close their doors temporarily. Among these were the First National Bank of Pittsburgh and Farmers National Deposit Bank, both at Fifth Avenue and Wood Street, and the People's-Pittsburgh Trust Company, at Fourth and Wood.

As telephones and electricity failed across downtown Pittsburgh, bank employees hastened to move bank ledgers and paperwork to areas that would remain above water. Some bank workers stood knee deep in water and worked by candlelight to close out their books.

Wood furniture at Colonial Trust Company (414 Fourth Avenue) and First National Bank (Fifth Avenue and Wood Street) was badly damaged by the flood and would subsequently be replaced.

Over the next two days, receding flood waters brought an unwelcome surprise to the officers and employees of many downtown banks with underground vaults.

They discovered that, in spite of vaults being sealed shut, concrete construction components were porous and had allowed flood waters inside, compromising some of the contents of customers' safe deposit boxes.

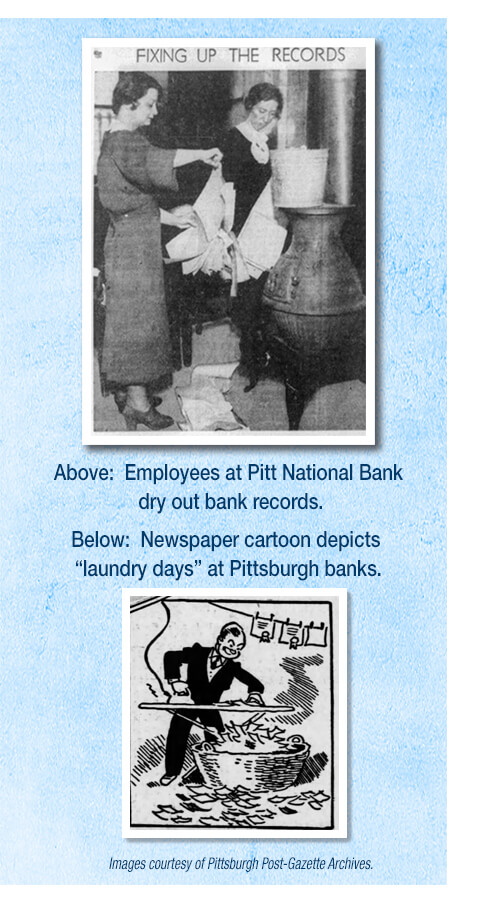

Paper-based materials such as stock and bond certificates had to be hung on lines like so much laundry until dry, and then ironed by the customer until free of wrinkles.

These "laundry days" at downtown banks extended into April and involved thousands of safe deposit box holders. One customer managed to restore a prized possession -- a letter written to him by Theodore Roosevelt.

The era of manual typewriters and ink stamps had its advantages. Although electricity was not restored to downtown Pittsburgh for several days after the flood, many banks were still able to serve their customers because their banking halls were illuminated by natural light.

Some banks, however, were not as fortunate. The Union Trust Company operated by candlelight until electric service was restored, and Pitt National Bank (Fifth and Liberty Avenues) was forced to temporarily relocate to the upper Triangle until their flood-damaged premises was cleaned up.

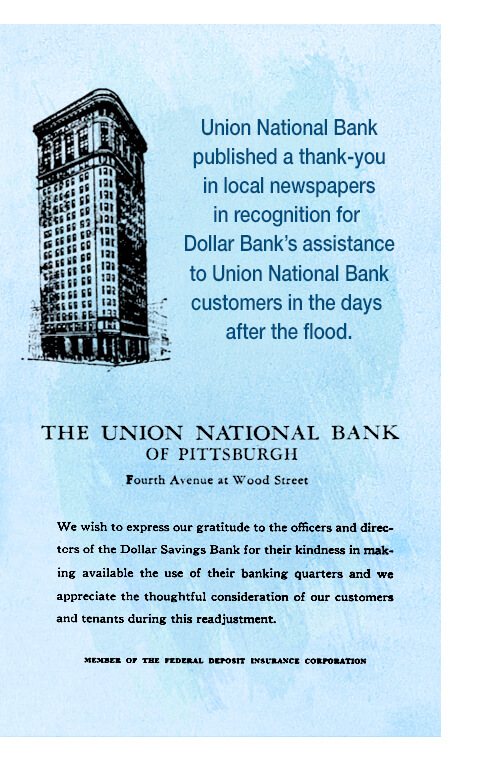

In the spirit of neighborly cooperation, Dollar Bank opened two teller windows to assist customers of Union National Bank after the latter's premises at Fourth and Wood Streets had been badly damaged in the flood. Customers of Union National were able to cash checks, make deposits, and pay mortgages and rent.

In gratitude, the officers and directors of Union National Bank wrote a thank-you letter to their counterparts at Dollar Bank, and also published a thank-you message in local newspapers.

Dollar Bank's New Vault

As a result of the St. Patrick's Day Flood, the importance of waterproof vaults was not lost on Pittsburgh's banking community.

Farmers Deposit National Bank spent $300,000 to install a new safe deposit vault in the summer of 1936. Located 14 feet above their main floor, the vault was designed to be beyond the reach of any flood waters up to the 60-foot stage. Pitt National Bank followed suit with a waterproofed safe deposit vault on their main floor in December 1936, while Colonial Trust Company waterproofed their vault as part of major renovations to their building in 1937. Union National Bank built a waterproof wall around its vault, and Keystone National Bank added bulkheads to protect its vault up to a flood crest of 54 feet.

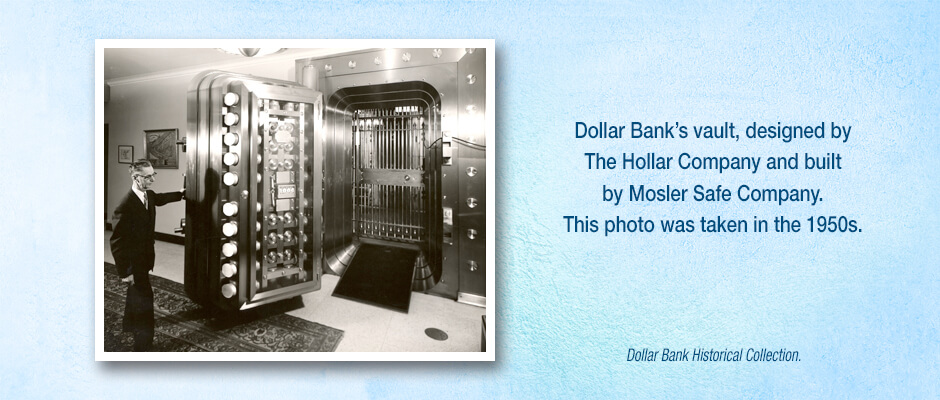

During their July 1937 meeting, Dollar Bank's directors approved the installation of a new vault in the bank's Fourth Avenue Building. Designed by Philadelphia-based vault engineers, The Hollar Company, and manufactured by The Mosler Safe Company of Ohio, the new vault measured 15 by 18 feet and featured copper plates sandwiched between steel walls, an extra security feature to protect against acetylene torches. The vault cost $100,000 and was installed by local construction company W.F. Trimble & Sons.

During their July 1937 meeting, Dollar Bank's directors approved the installation of a new vault in the bank's Fourth Avenue Building. Designed by Philadelphia-based vault engineers, The Hollar Company, and manufactured by The Mosler Safe Company of Ohio, the new vault measured 15 by 18 feet and featured copper plates sandwiched between steel walls, an extra security feature to protect against acetylene torches. The vault cost $100,000 and was installed by local construction company W.F. Trimble & Sons.

The two-tone, Art Deco styled vault is still in service at Fourth Avenue today.