Investing in Community, Businesses and People

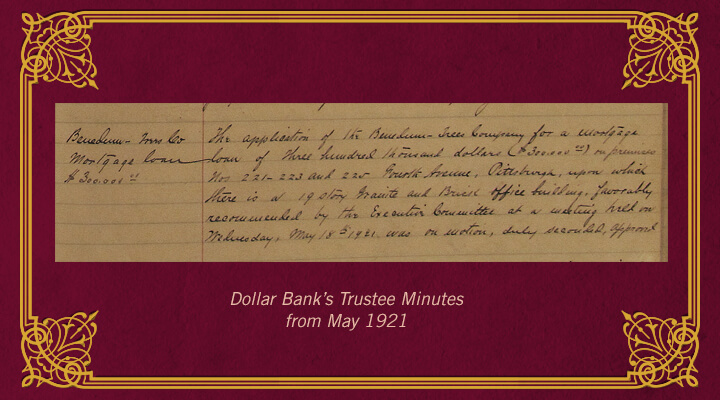

Benedum-Trees Oil Company Loan

Among the mortgages issued by Dollar Bank in 1921 was a loan for $300,000 to the Benedum-Trees Oil Company on the company's headquarters building on Fourth Avenue.

The iconic building at 223 Fourth Avenue in Downtown Pittsburgh has been known as the Benedum-Trees Building for more than a century. When it was completed in the spring of 1906, however, it was known as the Machesney Building and at 19 stories was one of the city's earliest skyscrapers. Among its first tenants were mining companies, brokers and bond traders, indicating the closely allied fortunes of industry and finance in early 1900s Pittsburgh.

The unusual origins of the Machesney Building were that it was owned by a woman, Mrs. Caroline Machesney, wife of attorney Allen Machesney. Mrs. Machesney, reported the Pittsburgh Daily Post on July 27, 1905, "was compelled yesterday to take out a building permit to shore up the walls of the stock exchange which adjoins her property."

In 1913, Mrs. Machesney was faced with the need to raise a large sum of cash to settle a legal dispute. She put the Machesney Building up for sale. In one of the biggest Pittsburgh real estate deals of the year, the property was bought by the Benedum-Trees Oil Company for $1,000,000, constituted in part by cash and in part by 1,000 acres of West Virginia coal land. This was the first skyscraper in Pittsburgh to change hands in a real estate purchase.

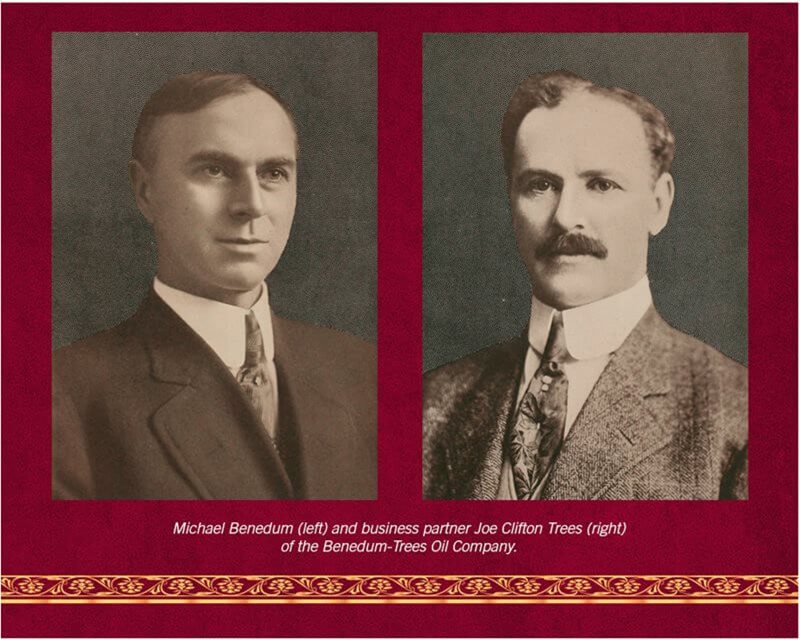

The partners behind the Benedum-Trees Oil Company name were Michael L. Benedum and Joe Clifton Trees. Benedum was a Bridgeport, West Virginia native without much formal schooling, while Trees, born in Delmont in Westmoreland County, got a football scholarship to Western University of Pennsylvania (University of Pittsburgh) and graduated with an engineering degree in 1895.

The storied wildcatting partnership between Benedum and Trees started in Pleasants County, West Virginia in 1896. The partners set up offices in Wheeling in 1904 and established a Pittsburgh presence in 1906 at 335 Fifth Avenue. The following year they moved their company into the then-new Union Bank Building at the corner of Fourth and Wood. With success came growth, and the Benedum-Trees Oil Company's purchase of the Machesney Building in 1913.

Regarding Dollar Bank's $300,000 mortgage loan to Benedum-Trees in May 1921, it's unclear what specific purpose the funds were put to, since the company already owned the building. It's conceivable that the money was used to make improvements to the 15-year-old property, although the Pittsburgh papers at the time made no mention of such. Around 1914, shortly after they purchased their new headquarters, Benedum and Trees entertained plans to add stories to the building, due to the demand for office space at the prestigious address. However, it appears an actual expansion was never performed.

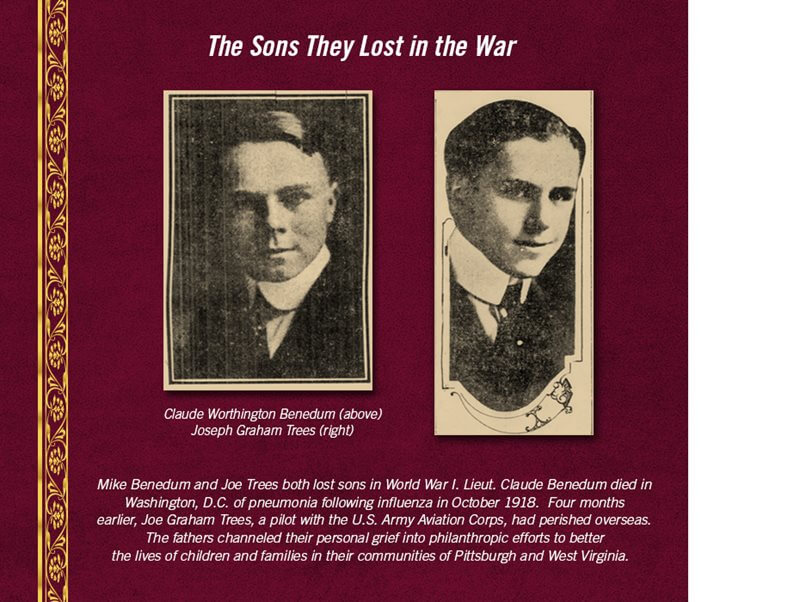

Mike Benedum and Joe Trees remained business partners for nearly half a century, until the latter's death in 1943. Both acquired massive fortunes in the oil business, becoming multimillionaires in less than 10 years. They made oil discoveries throughout the United States and in countries all over the world.

Both men donated generously to philanthropic causes. Trees became a major benefactor of the University of Pittsburgh and its athletics programs, as well as the Boys Club of Pittsburgh and National Park Seminary at Forest Glen, Maryland. Trees opened his personal home in Pine Township to Boys Club members every summer.

Benedum and his wife Sarah started the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation in 1944, in honor of their only son, who had died in 1918. True to his roots, Benedum focused the Foundation's charitable efforts on his home state of West Virginia, and his adopted home of Pittsburgh. To date, the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation has authorized more than $400 million in grants to education, economic and community development, and health and human services programs in those regions.

Disaster Relief in Response to the Chicago and Midwest Fires, 1871

The city of Chicago was not the only Midwestern community whose residents suffered from a catastrophic fire on October 8, 1871. The same night, the lumber town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, was destroyed by a wildfire, and three Michigan towns – Holland, Manistee and Port Huron – also burned.

October 1871 was a bad month for fire conditions in the Midwest. An exceptionally dry season and strong winds had Wisconsin citizens fighting forest fires in the early part of the month, and the western route of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railroad was plagued by fires. A Minnesota prairie fire made front-page news in Pittsburgh on October 7th.

The calamity that struck Chicago the following day, however, exceeded those earlier events in both scope and newspaper coverage. The conflagration raged for two days and burned more than three square miles of the city. Among the victims of the fire were around 300 Chicago residents, countless animals, and Lincoln’s handwritten draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was destroyed when the headquarters of the Chicago Historical Society went up in flames.

As soon as the first headlines announced the tragedy unfolding in Chicago, Pittsburghers thronged the newspaper and telegraph offices on Fifth Avenue, seeking updates. They learned that disaster had also struck Wisconsin and Michigan. The town of Peshtigo had been obliterated in a firestorm that burned an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Anywhere from 800 to 2,500 people lost their lives. In Michigan, the fires were plural and the communities ravaged were many. Millions of acres burned. The winds driving the flames were so strong that debris from the Holland fire was later found twenty-five miles away.

Pittsburghers responded to the disasters immediately. The terrible fire that had laid waste to Pittsburgh in 1845 was still within living memory of many residents. Citizens filled City Hall for a town hall meeting just one hour after the the mayor had called for the assembly. Pittsburghers elected a relief committee to oversee the city's official efforts, while countless organizations of private citizens got to work gathering supplies and donations for the stricken.

At 5:00 A.M. on October 10th, Pittsburgh Mayor Jared Brush received an urgent telegram from Chicago’s mayor pleading for firefighting assistance. City firefighters were roused by messenger. By 8:30 A.M., eight steam-powered fire engines and forty firefighters were on their way to Chicago via the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago Railroad. Fire Chief Engineer Crow of Allegheny City was in charge of the group.

Cash contributions poured in to the Chicago and Northwestern Relief Fund, swelling to $50,000 in just a few days. (The country’s Midwest was referred to as the Northwest in that era.) Clothing and provisions were also donated in abundance. The Ladies’ Relief Society gathered and packed clothes, and furnished volunteers who made clothing on sewing machines loaned by businesses around town.

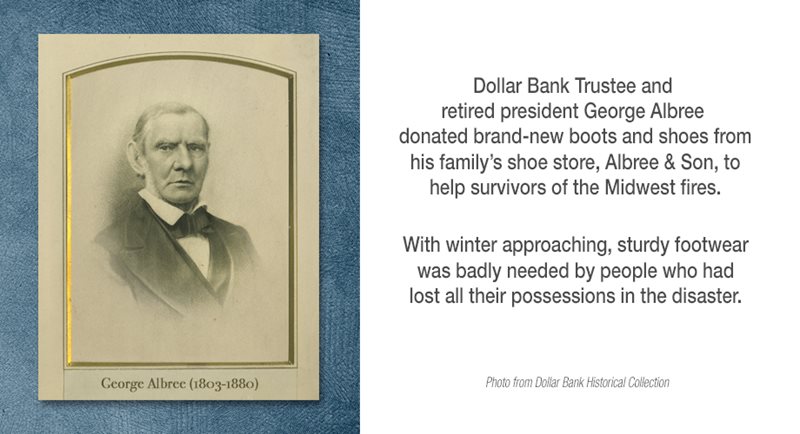

Local merchants were similarly generous. Grocer Thomas C. Jenkins donated 500 barrels of roasted coffee. Other grocers contributed beef, ham, bread and crackers. Dollar Bank Trustee and retired president George Albree donated boots and shoes from his family’s shoe store, Albree & Son, located on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Wood Street.

By the morning of October 11th, all these provisions, which included more than 3,000 loaves of bread and 2,000 pounds of bologna, were on an express train en route to Chicago. Accompanying the supplies were Henry B. Hays, one of the trustees of Pittsburgh's relief committee, John B. Hare, chief engineer of the volunteer fire department, and Mayor's Clerk James Patterson. The three men had been entrusted custody of $20,000 in cash from the City of Pittsburgh.

The assistance rendered on the mornings of October 10th and 11th was only the first of many efforts made by Pittsburgh residents over the next several weeks. Contributions were solicited for the rest of October, with special emphasis in follow-up efforts given to gathering aid for the people in Michigan and Wisconsin who had been affected by the fires.

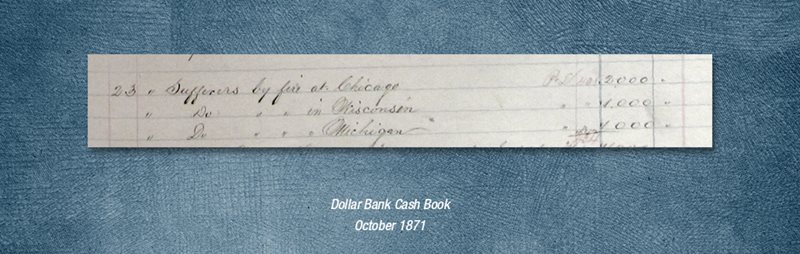

On October 23, 1871, Dollar Bank donated $4,000 to the Chicago and Northwestern Relief Fund -- $2,000 to the people of Chicago, and $1,000 each to the afflicted in Wisconsin and Michigan. This amount was the most given by any of the twenty-four Pittsburgh banks that contributed to the fund.

Disaster Relief in Response to the Johnstown Flood, 1889

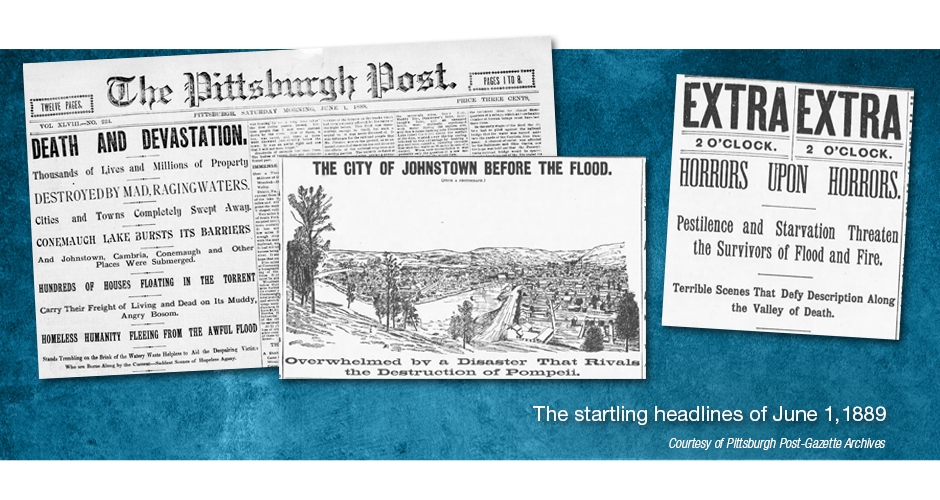

When Pittsburghers woke up on the morning of Saturday, June 1, 1889, they opened their newspapers and were confronted with reports of a terrible calamity less than a hundred miles away. The previous afternoon, the South Fork Dam in the Conemaugh Valley had suffered a catastrophic failure after 24 hours of heavy rainfall. More than 20 million tons of water were unleashed on communities below the dam. The torrent, which picked up debris and became an avalanche of everything, proceeded to smash the villages and towns of Mineral Point, East Conemaugh, Cambria City, Franklin and Woodvale.

Then, less than an hour after the dam broke, the raging water roared into Johnstown, an industrial city of 30,000 people. Fewer than 15 minutes later, all traces of modernity, and the life it supported, had been wiped from the city -- bridges, railroad tracks, telephone and telegraph poles, the Cambria Iron Works, stores, churches, schools and houses. The devastation was complete. More than 2,200 people lost their lives, and 1,600 homes were destroyed.

The catastrophe struck close to Pittsburgh not merely because of geographic proximity and residents who had friends and relatives in the stricken city. There was also the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, the exclusive organization with members such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick who came from the pinnacle of Pittsburgh society. The club had owned the dam that failed.

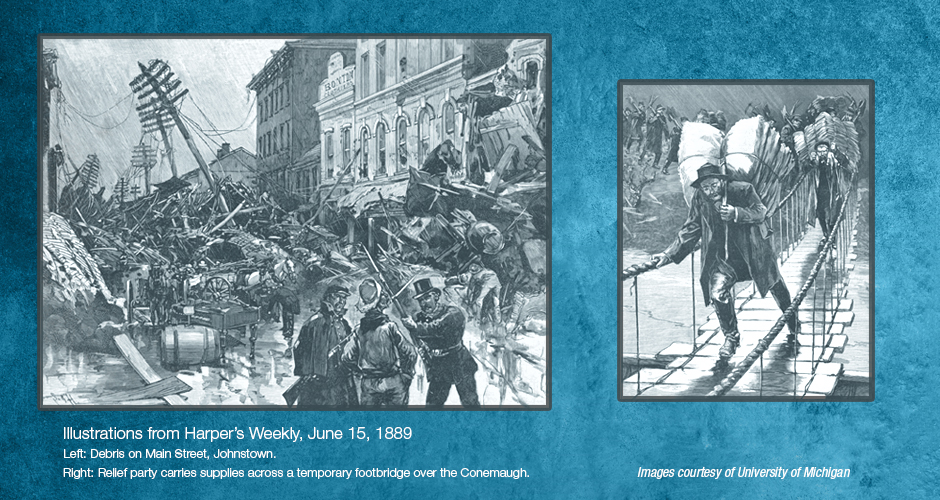

The response to the disaster from the citizens of Pittsburgh was swift. Pittsburghers formed a Citizens' Relief Committee to collect badly needed supplies for the relief of flood survivors -- food, clothing, fresh water, medicine, tools and household goods, wagons and wheelbarrows, and cash. Labor crews from local construction companies headed for Johnstown to help clear the massive debris that choked the streets of the ravaged city. Telegraph communication was restored between Johnstown and Pittsburgh by June 3rd, and the Citizens' Relief Committee of the latter had a telegraph installed at the chamber of commerce with a full-time operator.

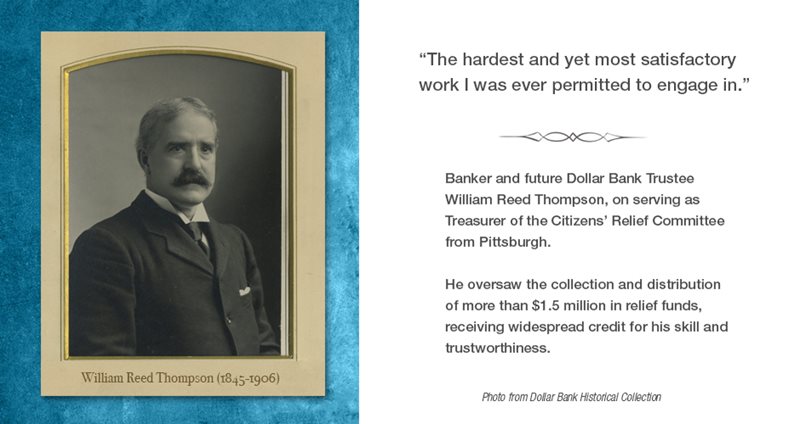

As cash contributions from Pittsburgh residents poured in, William Reed Thompson, banker and future trustee of Dollar Bank, was appointed treasurer of the relief fund. Ultimately the relief fund collected in Pittsburgh would grow to more than $1.5 million, or more than $40 million in today's dollars.

Contributions were published daily in local papers. The list of donors published in the Citizens' Relief Committee report of 1890 demonstrated how help came from every quarter of the Pittsburgh community.The nine Westinghouse Companies contributed $15,000. The Bijou Theatre held a benefit show. Iron and steel manufacturing companies donated. Employees from street car companies, railroads and the Carnegie Free Library gave. More than 150 churches and synagogues from Pittsburgh and Allegheny City contributed, as did hundreds more communities of faith from Allegheny and surrounding counties. The city's ten newspapers ran subscription drives for the relief fund. The 1890 report mentions a "Lady at City Hall door" who gave $2.00, and a "little six year old boy" gave twenty-five cents.

The scale of the disaster at Johnstown drew relief efforts from across the country, and even an international response. The relief fund in Pittsburgh received $3,000 from the City of Cleveland, donations from every state in the union, and contributions from groups in Australia, Brazil, Canada, England and Germany.

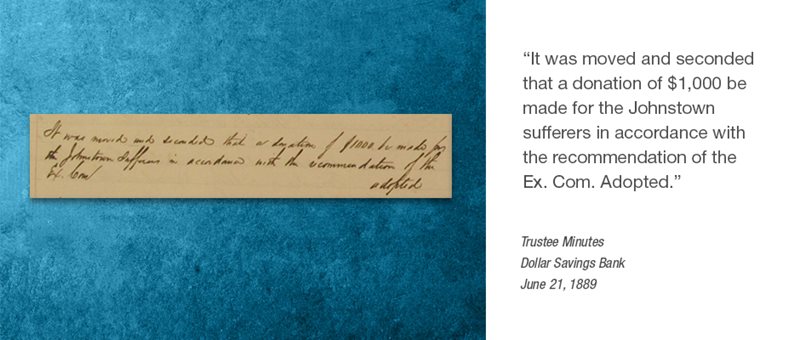

Forty-eight banks in Pittsburgh donated to the relief fund. On June 21, 1889, Dollar Bank's board of trustees approved a resolution to contribute $1,000 to the relief fund for Johnstown.

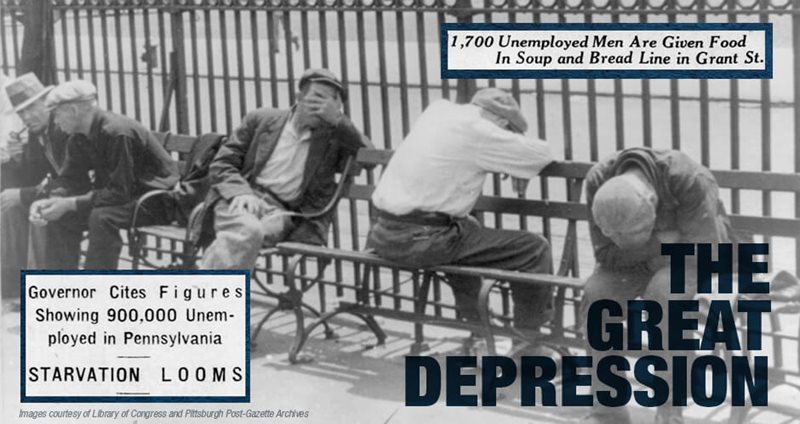

Dollar Bank's Contributions to Job Relief During the Great Depression

Job Relief

The Great Depression hit Allegheny County hard. The unemployment rate was 31.2% in 1931. Steel mills were operating at 46% average capacity, with a low of 25% in December 1930. The crisis of widespread joblessness was crushing many families and communities. Shantytowns of unemployed people sprang up in the Strip District, on Banksville Road, and in other locations around the city.In February 1931, Allegheny County business and civic leaders approved a jobs project called The Pittsburgh Plan. The goal was to raise $3 million to hire 20,000 unemployed local residents for public works projects such as paving roads and repairing and improving sidewalks, sewers, potholes and park entrances. Construction and repair work would benefit more than seventy towns and boroughs all over the county, as well as improving the facilities of hospitals, museums, libraries and charitable institutions.

The job relief program was run by the Allegheny County Emergency Association, a private-sector organization staffed by dozens of leaders from local firms. Among those on the Executive Committee were industrialists I. Lamont Hughes (Carnegie Steel Company), Howard Heinz (H.J. Heinz Company) and A.L. Humphrey (Westinghouse Air Brake Company), bankers Arthur E. Braun and William S. Linderman, contractor John F. Casey, merchant Edgar J. Kaufmann, and F.J. Chesterman of Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania. Auditing the enterprise was C.P.A. firm Richter & Co.

The Emergency Association worked with remarkable speed. Business leaders met with Pittsburgh Mayor Charles Kline on January 26th, announced their fund-raising plans on February 3rd, and had hired nearly 200 men by the last week of February. By summer 1931, employment through the program was given to more than 6,700 people, both male and female.

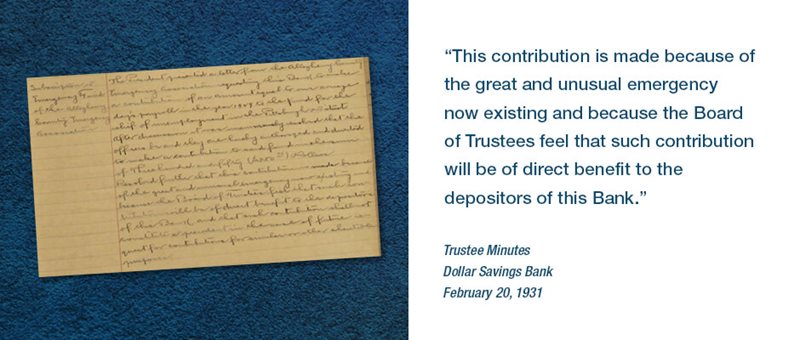

Local businesses voluntarily pledged subscriptions pegged to company payrolls from 1929. Dollar Bank had 30 employees on payroll in 1929. The bank at that time was a very small organization with just one office (Fourth Avenue), and was dwarfed by the county's largest employers, which included Westinghouse with 30,000 employees, Carnegie Steel Company, 22,000; H.J. Heinz Company, 11,000; Kaufmann's, 3,200; Gimbel Brothers and Mesta Machine Company, 2,000 each; and Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, with 1,300 workers at just its Creighton plant. Duquesne Light Company employed 2,500 workers to run its facilities on Brunot Island.

Nevertheless, companies large and small worked together to form a local response to alleviate local needs.

Dollar Bank's initial contribution to the job relief Emergency Fund, made in February 1931, was $350.00, representing one day's payroll from 1929. Subsequent contributions were more substantial and were based on a percentage of operating costs. During the years that the job relief program existed, 1931-1934, Dollar Bank contributed $20,193 to the fund. That's more than $400,000 in today's dollars.

Community Fund

The Allegheny County Emergency Association wound down its work after 1934, having accomplished its stated goals from three years earlier. While the immediate crisis of local unemployment had been addressed, many county residents were still struggling in poverty. Pittsburgh's Community Fund for Charities, established in 1928 as the Welfare Fund of Pittsburgh, partnered with local social service agencies to assist the poor and needy. By 1937, the number of Allegheny County agencies receiving Community Fund contributions to carry out their work had grown to seventy-five.As with the Pittsburgh Plan's Emergency Fund, campaigns were run and donations solicited from individuals and businesses annually each November. From 1935 through 1940, Dollar Bank gave a total of $32,400 to the Community Fund, or more than $600,000 in current dollars.

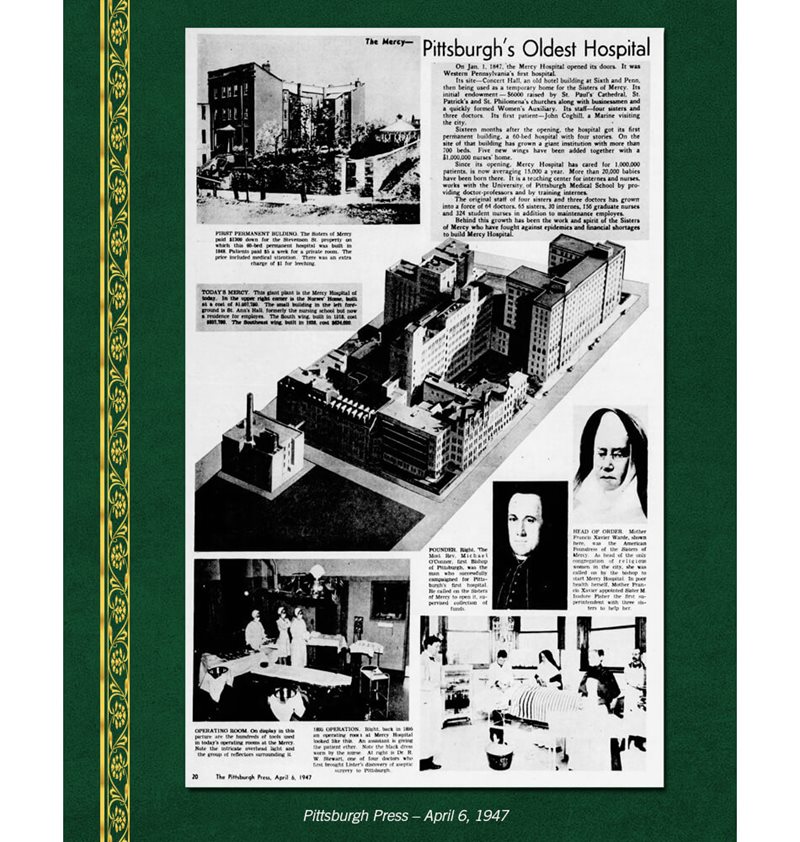

Helping Mercy Hospital Best Provide Care to Those Most in Need

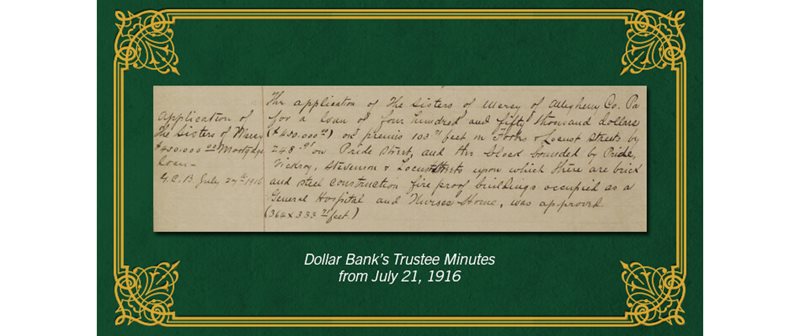

On July 21, 1916, Dollar Bank's Board of Trustees approved a loan of $450,000 to the Sisters of Mercy to help finance an expansion of Mercy Hospital. This enormous sum (equivalent to about $10 million today) was three-quarters of the project's $600,000 budget. The eight-story annex at Stevenson and Vickroy, later known as the south wing, added 100 private rooms, wards for 240 patients, a kitchen and dining rooms.

The first hospital in Western Pennsylvania, Mercy Hospital opened its doors on January 1, 1847, with a staff of four sisters and three doctors. During the hospital's first 100 years, the dedicated staff of Mercy cared for more than 1,000,000 patients and delivered 20,000 babies. The hospital's campus has grown up around the site of its first permanent building on Stevenson Street. Today it remains Pittsburgh's only Catholic hospital, providing care to those in need, with a special commitment to the poor and uninsured.

About the Sisters of Mercy

Founded in Dublin, Ireland in 1831 by Catherine McAuley, the Sisters of Mercy is a religious order of Catholic women committed to caring for and uplifting the poor, the sick, the orphaned and the uneducated. McAuley used her own inheritance to build a "House of Mercy" in Dublin, which she dedicated to Mary the Mother of Mercy, and from which she and other sisters carried out corporal and spiritual works of mercy serving the poor of the city.

The Sisters of Mercy established their first foundation in the United States in 1843, in the city of Pittsburgh, where the Most Rev. Michael O'Connor (1810-1872) had recently been appointed bishop of a new Catholic Diocese.

Mother Frances Xavier Warde (1810-1874) and the six sisters who accompanied her from Carlow, Ireland, to the then-frontier community of Pittsburgh, quickly made an impact on the growing city. In their first three years, they opened three schools and an orphanage.

In 1847, the sisters founded Mercy Hospital. Their courage and compassion was put to the test in the very first year, when a typhus epidemic struck the city. Four of the original seven sisters, serving as nurses in the hospital, died of the disease. Undaunted, the sisters nursed the stricken during a deadly cholera outbreak in 1854 in spite of the risk to their own lives. Sisters of Mercy were the only nurses at Mercy Hospital until 1895.

In 1929, the sisters founded Mount Mercy College, now Carlow University. Today, more than 11,000 Sisters of Mercy serve the poor and needy worldwide.

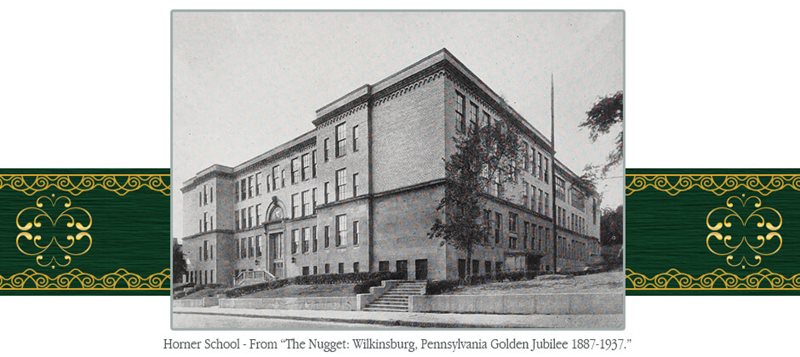

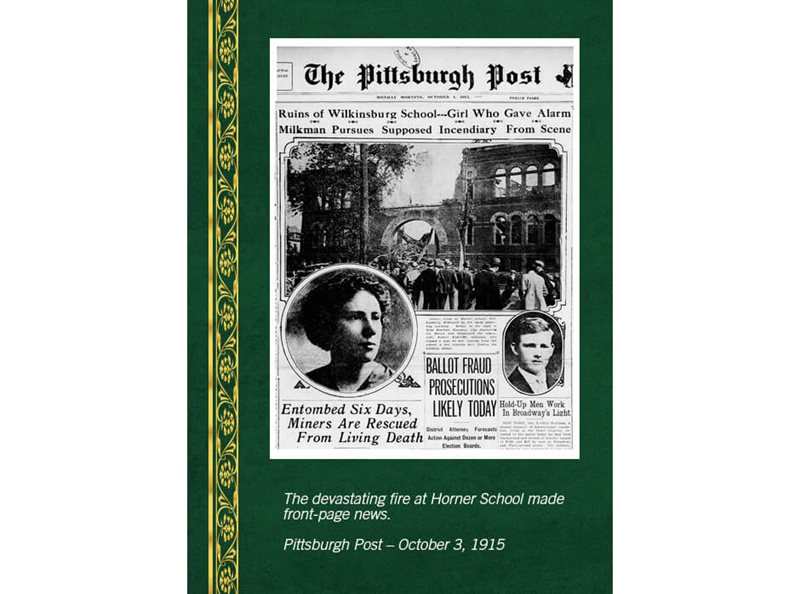

Rebuilding Horner School in Wilkinsburg

On the morning of October 3, 1915, residents of Wilkinsburg woke up to terrible news. Horner School, at Wallace and North Avenues, had been gutted by fire in a devastating overnight blaze, despite the efforts of firefighters from Wilkinsburg and City of Pittsburgh Fire Companies No. 16 and 29.

The ruined building and its contents were a loss of more than $65,000 for the school district. It was the second school building on that site, having replaced the original Horner School, also destroyed by fire in 1890.

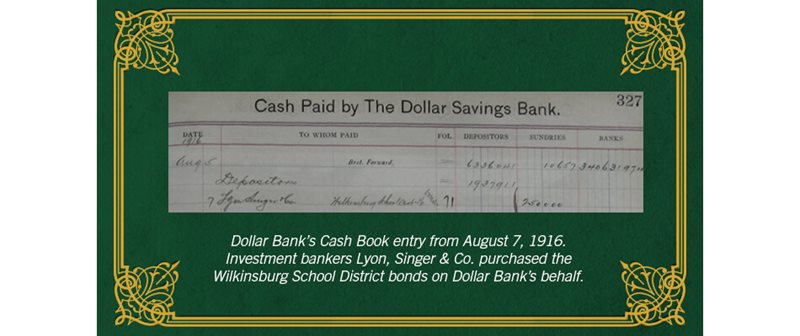

Horner's displaced students from the 1915 fire temporarily attended other schools in the district. In January 1916, Wilkinsburg citizens voted to approve a $250,000 bond issue to finance the construction of brand-new school building with all-modern facilities.

Dollar Bank purchased the entire bond issue in August 1916. Architects Ingram & Boyd designed the building, and general contractor Dawson Construction oversaw the project. On January 7, 1918, 650 grade schoolers and 660 junior high students walked through the doors of their new school, which boasted four stories of classrooms, a cafeteria, nurse's office, gymnasium and a swimming pool.

Today, the Horner School building constructed in 1917 is the home of Hosanna House, Inc.

Rodef Shalom's First Synagogue

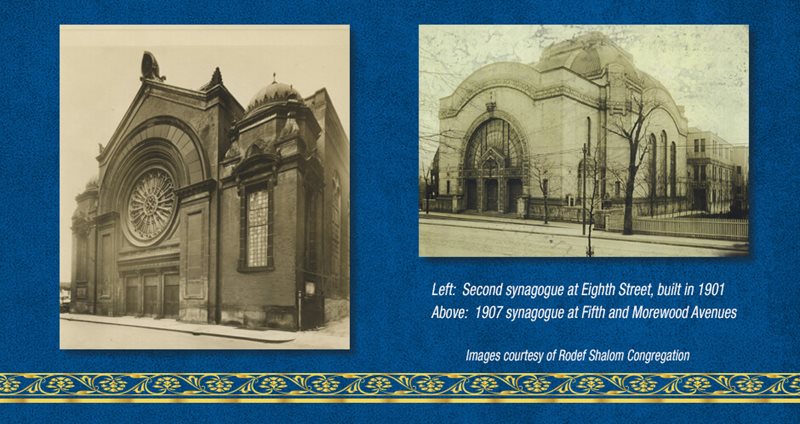

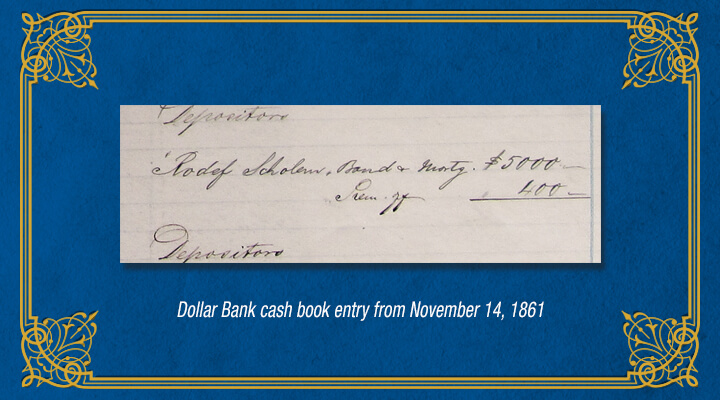

Founded in 1847 and chartered in 1856, Rodef Shalom was established by pioneers of the Jewish community in Pittsburgh. In the late 1850s, the congregation held divine services in a hall on Third Street, opposite the Vigilant Engine House. They then moved to St. Clair Street (now Sixth Street). By 1860, the congregation was eager to have their own house of worship, and they began the process of selecting property and raising funds for their future synagogue.

Construction began in early 1861, on a site on Hancock Street (Eighth Street). On November 14, 1861, Dollar Bank issued a $5,000 mortgage to the Rodef Shalom congregation as the building project, which cost around $35,000 total, continued apace. The following March, the newly completed building, the first synagogue in Western Pennsylvania, was consecrated. Designed by Pittsburgh architect Charles Bartberger, the building held about 700 people.

As the congregation grew, more space was needed to accommodate education and worship. In 1888, the synagogue underwent $10,000 in renovations and expansions, resulting in what the Pittsburgh Post called "one of the handsomest places of worship in the city." Frescoed walls and ceilings, carpeted floors, antique oak woodwork, new gas lighting fixtures and gallery seating were highlights of the renovations. A 72-burner gas chandelier was suspended from the ceiling in the center of the building.

The expansion of the synagogue in 1888 served the congregation for just over a decade. By 1900, it was apparent that a brand-new synagogue was needed. After fixtures and furniture were removed and preserved, the original edifice was demolished in late 1900, and a second building was constructed on the same site.

More change was right around the corner. As congregants moved to the East End, a synagogue located in downtown Pittsburgh made less and less sense. In 1905, Rodef Shalom sold its Eighth Street building to the congregation of Second Presbyterian Church and purchased a plot of vacant land at Fifth and Morewood Avenues in Squirrel Hill. Architect Henry Hornbostel designed the new synagogue, which was completed in 1907, and which still serves the members of Rodef Shalom today.

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall Construction Funding

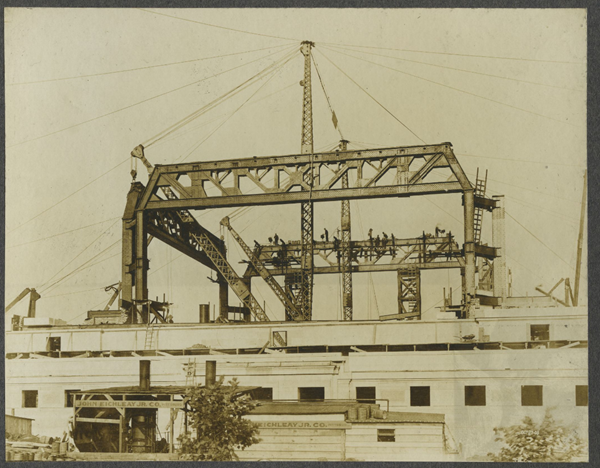

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall under construction c. 1910. Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Dedicated in October 1910, Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall was built to honor the Civil War veterans of Allegheny County. Around 26,000 men from Allegheny County served during that conflict. Today, the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum honors all area veterans who have served the United States throughout the country’s history.

The proposal for a memorial honoring Allegheny County soldiers and sailors who had served during the Civil War originated in 1891 during discussions at the monthly meetings of the Allegheny County Grand Army of the Republic Association. In 1903, a townhall was held for the public, including veterans, to discuss the merits of a Memorial Hall instead of a monument. A committee took a proposal to Harrisburg to permit public financing of a Memorial Hall. The Remedial Act was passed by Pennsylvania’s legislature in April 1903.

Architect Henry Hornbostel of the New York firm Palmer & Hornbostel designed the Memorial Hall. David L. Wright supervised construction. Sculptor Charles Keck created the bronze “Peace” statue that sits at a central spot over the Fifth Avenue entrance to the building.

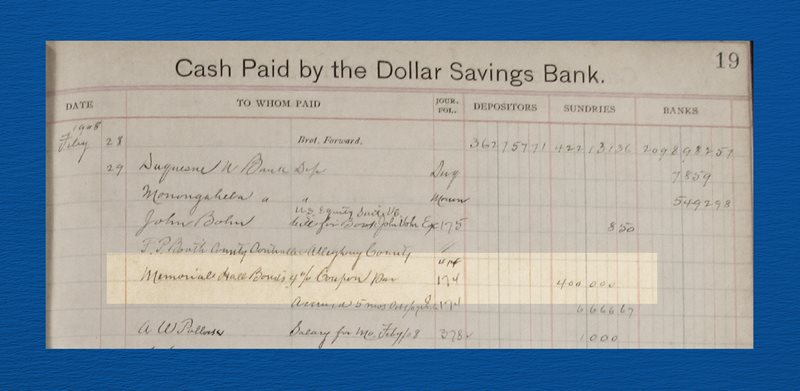

To fund the project, Allegheny County issued a series of bonds in 1907 and 1908 amounting to a total of $1.25 million. Dollar Bank purchased 55% of the bonds: $200,000 in September 1907, $400,000 in January 1908 and $100,000 in April 1908.

The dedication of the Memorial Hall in October 1910 was a grand multi-day event. Mayor William Magee proclaimed Tuesday, October 11, 1910 a city holiday so veterans, dignitaries and Pittsburgh residents could enjoy a parade and dedication service for the Memorial Hall.

Dollar Bank cash book entry recording the $400,000 bond purchase in early 1908. Dollar Bank Historical Collection.

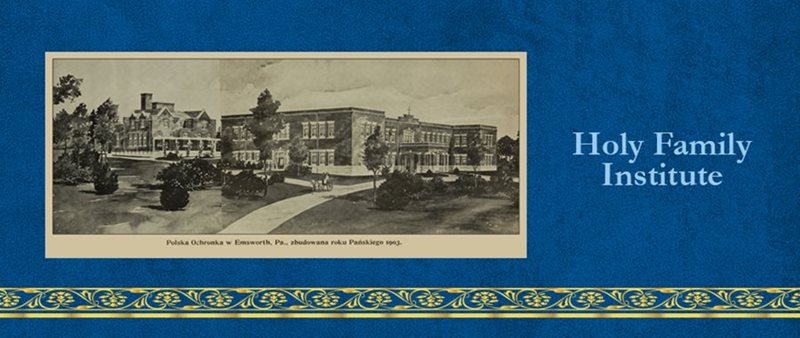

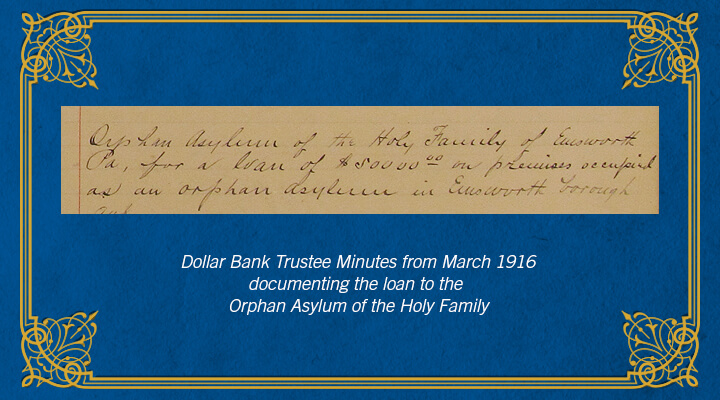

The Expansion of Holy Family Institute

In March 1916, Dollar Bank approved a $50,000 loan to the Orphan Asylum of the Holy Family, located in Emsworth. The loan helped fund an expansion of the institute's dorms and classrooms.

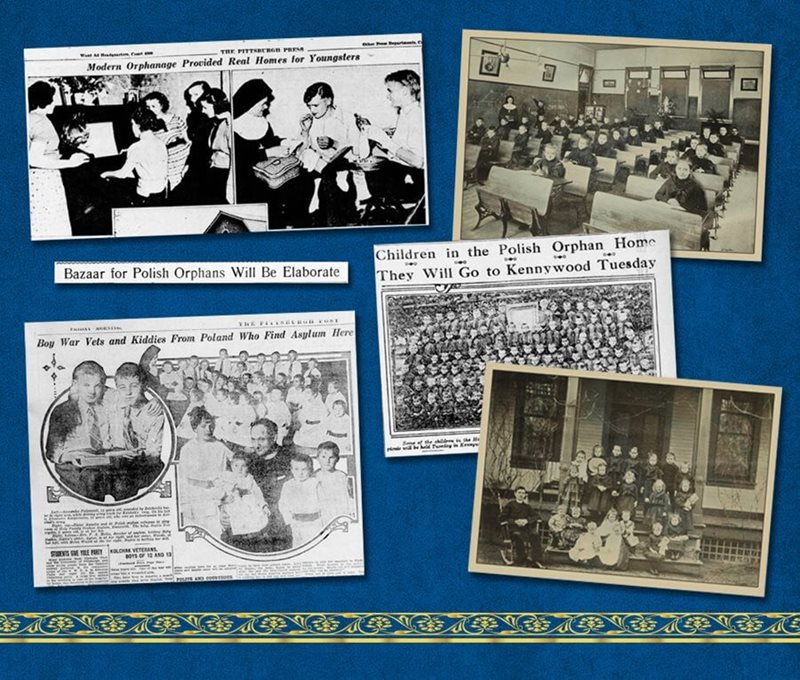

Founded in 1900 by the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth, under the directorship of Father Caesar Tomaszewski, the institute housed and educated anywhere from 250 to 400 children daily. It enjoyed a close relationship with the Polish-American community of Pittsburgh. Fundraisers were held regularly at Polish churches.

The orphans delighted in their annual trip to Kennywood, an event that coincided with "Polish Day" at the park, which drew nearly 5,000 people in 1915.

In addition to helping local children, the Orphan Asylum extended its mission to rescuing orphans from war-torn Europe. Polish and Russian refugee children found safety and shelter at the institute after being separated from their parents in the chaos of the First World War.

Father Andy Retka succeeded Fr. Tomaszewski as director of the orphan asylum in 1915. Both priests had studied at Holy Ghost College (now Duquesne University) and had served as pastors of St. Stanislaus Church in Pittsburgh.

In 1931, the Orphan Asylum of the Holy Family changed its name to Holy Family Institute. It continues to serve children and families in the Pittsburgh region to this day.

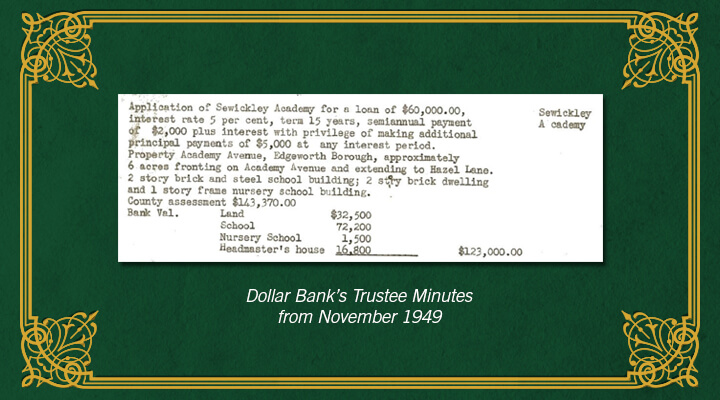

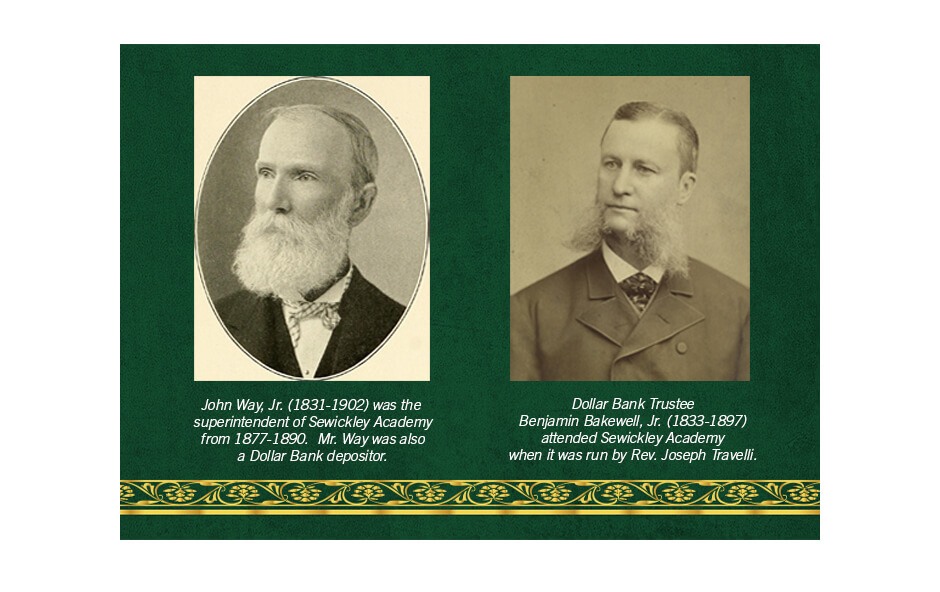

The Expansion of Sewickley Academy

The oldest independent school in Western Pennsylvania, Sewickley Academy settled onto its present campus on Academy Avenue in 1928 as a co-educational day school. After World War II, enrollment increased from 142 to 235 students, making expansion of the Academy's facilities a necessity.

Sewickley Academy's Board of Trustees approved the construction of a new three-story wing that would increase the school's space by 50 percent. The addition would include new classrooms, faculty rooms, a cafeteria, kindergarten, music room, library, a science room and laboratory. Rust Engineering Co. was selected to work on the project.

Prominent Sewickley residents launched a fundraising campaign in January 1949 to raise $200,000 to help fund the addition to the school. To supplement community fundraising, the Academy's directors also applied for a loan from Dollar Bank. In November 1949, Dollar Bank's Board of Trustees approved a loan of $60,000 to Sewickley Academy towards their building project.

Prominent Sewickley residents launched a fundraising campaign in January 1949 to raise $200,000 to help fund the addition to the school. To supplement community fundraising, the Academy's directors also applied for a loan from Dollar Bank. In November 1949, Dollar Bank's Board of Trustees approved a loan of $60,000 to Sewickley Academy towards their building project.

Groundbreaking took place the next month, December 1949, and the addition was rushed to completion in August 1950, just in time for the new school year. The addition allowed Sewickley Academy to increase its enrollment that term to 280 students, and enabled the exponential growth in enrollment in the following decades during the administration of headmaster Cliff Nichols.