George M. Schilling

1874 – 1920

One-armed athlete and daredevil George M. Schilling seemed like a character out of an adventure novel. His thrill-seeking promotional stunts included jumping off the Point Bridge in Pittsburgh and long-distance walks across the U.S. and around the world.

The son of German immigrants, Schilling grew up in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and attended the old Eleventh Ward public school at the corner of Granville and Enoch Streets. At age 9, he lost his left arm in an accident at an axe factory on what is now Dinwiddie Street. He earned money as a bootblack and newsboy to help supplement the family’s income.

As a teen, Schilling became involved in track and field sports and joined the Emerald Athletic Club. He first caught the attention of sports fans at the Fourth of July games at Schenley Park in 1892, competing in running broad jump and hop-step-jump events. Schilling became a fan favorite and competed in the annual games for the next several years, winning several medals and prizes.

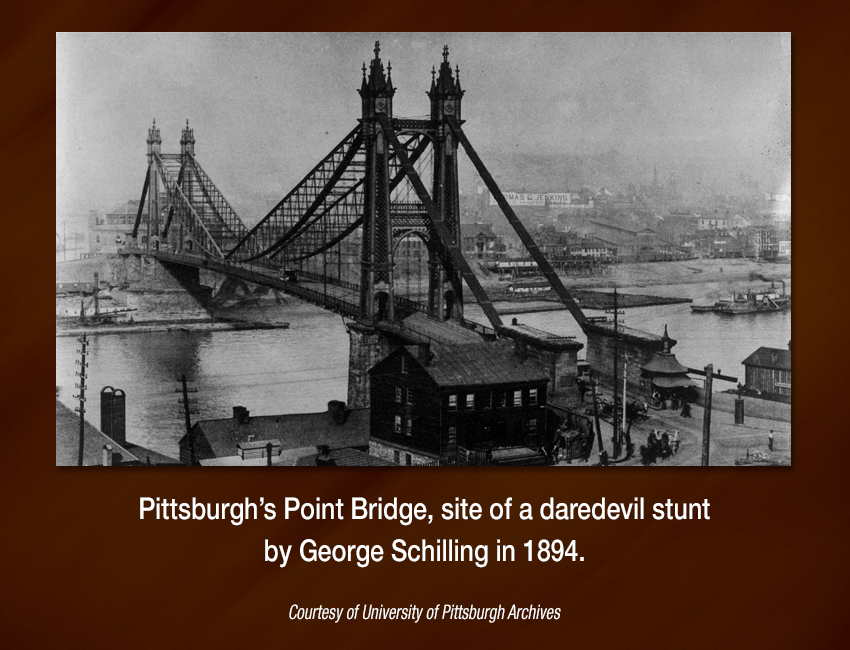

The bigger the challenge, the more Schilling was determined to compete. In the 1890s, bridge-jumping was a dangerous fad among often poor but plucky young men seeking fame, thrills and wager money. Steve Brodie was one such person who briefly leveraged his notoriety from bridge-jumping into musical theater appearances and popular celebrity. Pittsburgh, a city abundant with bridges, had no shortage of thrill-seekers. In November 1894, George Schilling took a $20 wager and jumped 110 feet off the Point Bridge into the Monongahela River, then swam his way to shore. Two years later, he thrilled a crowd by jumping 140 feet from the high bridge in Clinton, Iowa, into the Mississippi River. Fortunately for Schilling, he survived his bridge jumps (unlike several contemporaries) and switched to long-distance walking in his pursuit of record-making adventures.

In April 1895, George Schilling successfully completed the first of his long-distance walks. He set out to break the record, then 12 days, for walking from Pittsburgh to New York, a distance of 441 miles. His route would take him along the Greensburg Pike, across the state to Philadelphia, then north to New York City.

The curiosity factor of his adventure made for good newspaper copy. Schilling started out his walk at 9 A.M. on Monday, April 15th, in front of the Pittsburgh Press offices. He wore a mackintosh coat, sturdy walking shoes and a small knapsack. He carried no money, but he did bear blank cards to be signed by prominent citizens of the towns he passed through to verify his travels.

He reached Johnstown at 7 P.M. on April 16th, Altoona at 5:40 P.M. on April 17th, Harrisburg on the afternoon of April 19th (where he stopped by the offices of the Harrisburg Telegraph), and Philadelphia the evening of April 21st. He had walked across Pennsylvania in six-and-a-half days, at an average rate of 47 miles per day.

Nine days and one hour into his journey to New York City, Schilling reported in at the Manhattan offices of the Police Gazette, a men’s lifestyle magazine that also covered sports and record-setting competitions. George Schilling had broken the Pittsburgh-to-New-York amateur walking record by three days.

Schilling returned to Pittsburgh and competed in July Fourth games before a crowd of 40,000 spectators at Schenley Park, as well as an open-field meet of the Pittsburgh Athletic Club that September. He ran a 10 3/5 in the 100-yard dash at the latter event, coming in a split-second after R.A. Sterritt of the Pittsburgh Athletic Club.

On April 20, 1896, Schilling set off on an even more daunting journey than the year before, a long-distance walk from Pittsburgh to San Francisco and back. The $1,000 wager was backed by the Ellsworth Athletic Club. The first half of the route went through Ohio to Chicago, then to Omaha, Cheyenne and Ogden before winding up in California.

In addition to the physical exertion of the trip itself, Schilling had two more challenges to meet – to complete the 7,500 round-trip expedition in ten months, and to return with $1,000 in cash earned from sports competitions, daredevil wagers and odd jobs along the way. (Food donations were allowed, but panhandling for cash was against the rules of the endeavor.)

Schilling took a dog as his traveling companion. His first dog, a St. Bernard, could not endure the exertion, so Schilling was gifted a foxhound by the citizens of Alliance, Ohio. King the foxhound (originally named Coxey) not only made the rest of the cross-continent trek with Schilling but also accompanied him on subsequent long-distance walks.

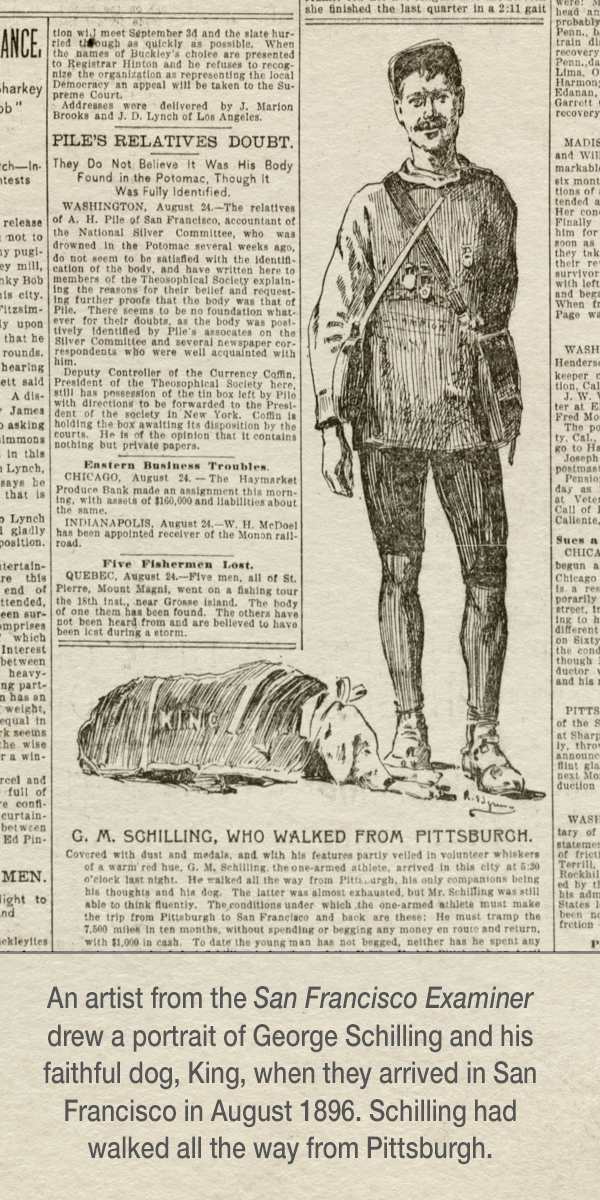

Schilling and King made it to Laramie, Wyoming on the Fourth of July, Salt Lake City on July 24th, then arrived in the offices of the San Francisco Examiner at 5 P.M. on August 24th. The Examiner described the pair of travelers as “almost exhausted” but that Schilling “was still able to think fluently.” The six-foot-two athlete sported “volunteer whiskers of a warm red hue.” The good news was he was nearly a month ahead of schedule, but the bad news was that he had less than a quarter of the cash he needed to raise on the trip.

After a few weeks of some well-deserved rest, Schilling and King left San Francisco on September 15th, with a card from the city clerk’s office certifying the date and time of their departure. They returned to Pittsburgh by way of Portland, Butte, Denver, St. Louis, Cincinnati and Wheeling, taking a longer route back to avoid the desert. The pair arrived in Pittsburgh at 3 P.M. on February 18, 1897, to a hero’s welcome. Enthusiastic crowds cheered on Schilling and King as they crossed the Smithfield Bridge to downtown. King was bedecked with a festive ribbon for the occasion.

“He is a powerfully built young man,” the reporter for the Pittsburg Dispatch described Schilling, “and there is no doubt about his honesty in the performance of the feat. His looks betoken a lot of hardships, and his tales of the trials and tribulations gone through during his remarkable walk fully correspond with his general appearance.”

The crowd followed Schilling and his dog to the offices of the Pittsburgh Post. “Schilling looks in splendid shape, and appears much bigger and stronger, and certainly more tanned than he did nearly a year ago when he began his tramp,” the newspaper noted. Schilling had worn out 22 pairs of shoes on his trek.

George Schilling had a harrowing tale for the newspapers when he gave interviews upon his return. He said the harshest part of his journey had been the stretch across the Great Basin Desert. In one instance during the cross-continent trip, King had become unable to walk, and Schilling towed his dog on a board behind him, unwilling to leave his devoted companion. Schilling said he was grateful to all he had met who had treated him well, especially the Chinese railroad laborers who had generously shared their provisions of rice and tea with him.

Schilling’s journey had taken 282 days total – 126 to reach San Francisco, and 156 for the return – and he made it back to Pittsburgh two days ahead of his 10-month goal. Unfortunately, he was a few hundred short of the $1,000 purse he had aimed to raise along the way.

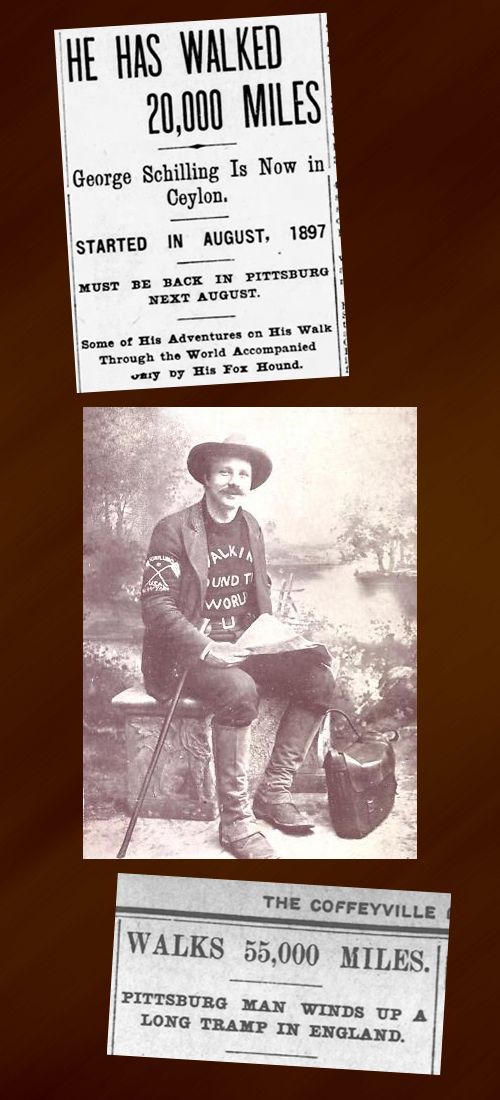

Although Schilling maintained upon his return to Pittsburgh that he was retiring from long-distance walking, it was only a matter of months before he undertook his next expedition – an attempt to walk around the world in four years. The reported potential prize was $10,000 in wagers if Schilling could complete the journey.

He made the official start on August 2, 1897, from New York City, headed west through the Great Lakes States following railroad routes, then turned south for warmer weather as he aimed for San Francisco, where he intended to sail for Australia. Due to the difficulty of finding passage on a ship that would allow him to take his dog with him, Schilling ended up walking to Vancouver and set sail from that city.

Savvier this time about the value of visuals and newspaper photos in promoting his adventure, Schilling dressed the part of a world traveler. Literally. He wore a cap with the words “Champion Walker” embroidered on it and a blue sweater with the emblem, “Walking Round the World.” His knapsack was full of picture postcards of him in his traveling gear. He sold these along the way to earn money for food and boat passages. His dog, King, accompanied him.

Schilling’s walk-around-the-world expedition bore the hallmarks of a man who was one part showman and one part endurance athlete. It appears that Schilling successfully traveled to and did long-distance walks in countries on five continents, but also that reports of miles covered and adventures along the way were embellished.

Long periods of silence punctuated by sporadic letters from Schilling to the Pittsburgh newspapers and his friends made it difficult to maintain a constant record of where he was during his travels. He spent 1898-1900 walking Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania. In November 1900 he reached Ceylon. He also reported having walked across India, from Calcutta to Bombay, before traveling through Rangoon, Mandalay and Singapore.

He reappeared in April 1901 in Hong Kong, presenting himself at the U.S. Consulate on April 17th. The next two months he spent walking through Japan. He claimed difficulty walking through China, South Africa and Turkey due to volatile political situations, but he succeeded in visiting Egypt. By 1904 he was in Europe, sending reports from Monte Carlo (January 1904), Genoa, Italy (May 1904) and Berlin (August 1904).

To document his travel route, Schilling kept books with stamps and certificates from the places he had passed through, using consulates and post offices to procure the certifications. Schilling's books were too valuable and numerous to carry with him on his long-distance walks, so he left the books in secure storage in port towns when he arrived in countries on his route, and reclaimed the books when he departed.

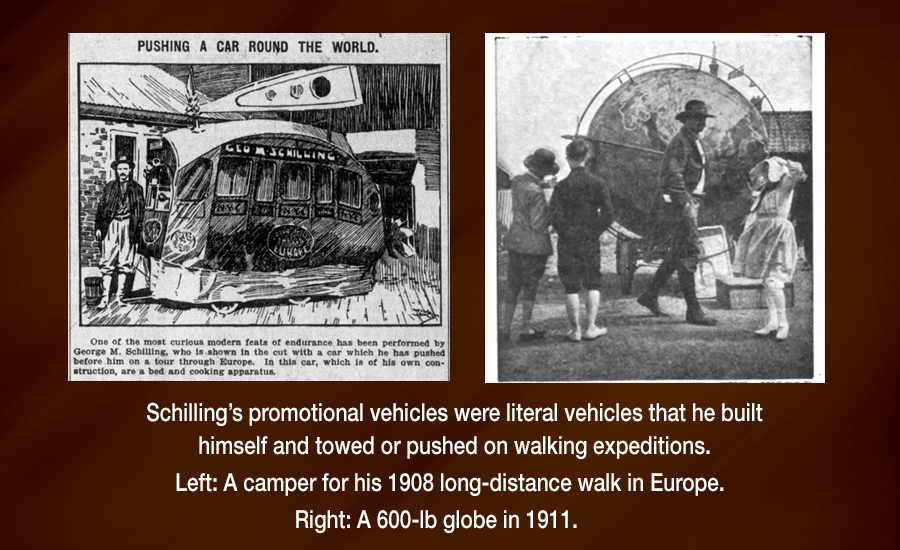

Schilling reached England in January 1905 and walked from Southampton to Bristol to Liverpool to Newcastle upon Tyne, then to Kingston upon Hull, where he met and married drapery shop assistant Ellen May Matthews. The couple remained in the U.K. for the next decade, a base from which George Schilling made at least two more walking tours of Europe in 1908 and 1911.

The Schillings and their four children moved to Pittsburgh around 1917, where they settled on Laclair Street in Edgewood. A fifth child was born in Pittsburgh. George Schilling gave lectures and sold books about his travels and the sport of long-distance walking. He died in May 1920 and received a lengthy obituary in the Pittsburgh sports pages.

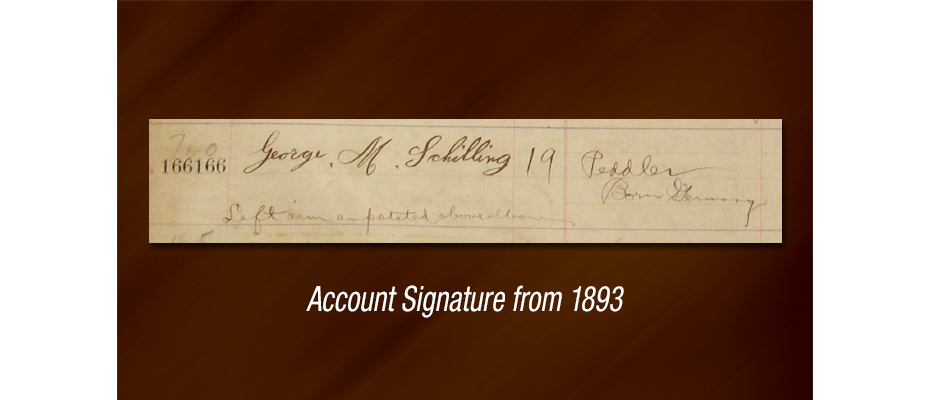

George M. Schilling opened a savings account at Dollar Bank in October 1893.