Captain Bill Jones

A Steelworker's Steelworker

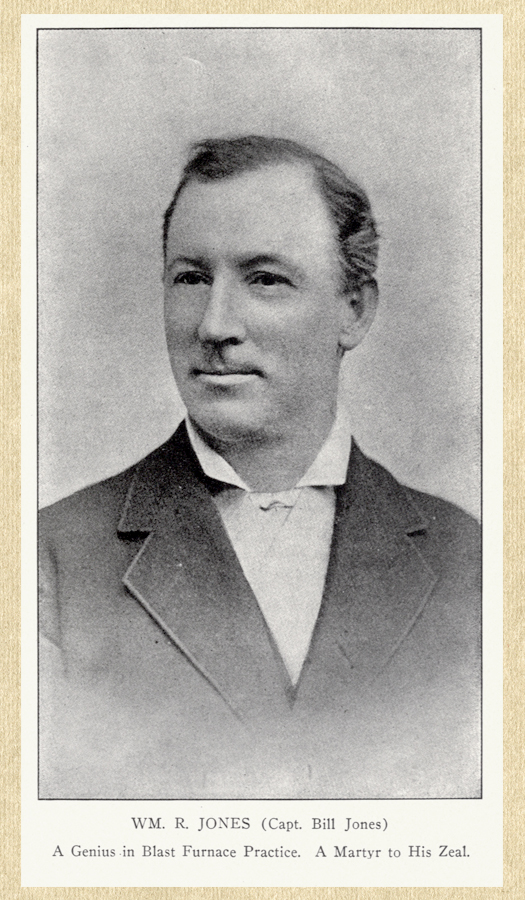

William R. Jones (1839-1889), also known as Captain Bill Jones, was a steelworker and inventor whose leadership and intimate knowledge of the steel-making process were critical to the early success of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, Pennsylvania.

A full generation after Jones had passed from the scene, Harper’s Weekly dubbed him “the greatest master of steel-making that the United States has ever seen.”

Author and editor James Bridge Howard, who spent five years as Andrew Carnegie’s literary assistant and who wrote the 1903 book The Inside Story of the Carnegie Steel Company, called Bill Jones “probably the greatest mechanical genius that ever entered the Carnegie shops.” From the outset, Jones was “the most conspicuous personal element in the phenomenal success” of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works.

Jones’ tremendous understanding of both men and machines, combined with a deep reservoir of virtues such as honesty, forthrightness and courage, earned him the respect of the men he worked with and the recognition of historians who have written about the early years of the steel industry in the United States.

Early Life

Born in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, Bill Jones was the seventh of eleven children of poor Welsh immigrants. Jones lost both his parents early in his life – his mother, Magdalen, when he was eight, and his father, Rev. John G. Jones, when he was fourteen.

Jones was already working by the time his father died, having been apprenticed at age ten to the Crane Iron Company in Catasauqua (Lehigh County). Under the instruction of mechanic and later chief engineer Hopkin Thomas, Bill Jones developed the machinist skills that would carry him far in life. By age fourteen, Jones was earning the full wages of a journeyman.

Jones was employed at several more machine shops in Pennsylvania until he found himself out of a job during the financial panic of 1857. He switched trades, laboring as a lumberman and farmhand until returning to industrial work in late 1858.

In the spring of 1859, he was hired as a machinist at the Cambria Iron Company in Johnstown, where he attained the rank of master mechanic. When the company expanded with the construction of a blast furnace in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Jones moved south to work on the project.

He was still in Tennessee, and a newlywed, when the Civil War erupted in April 1861. A staunch Unionist, Jones returned to Pennsylvania with his wife and resumed his work in Johnstown at the Cambria Iron Company.

The following year, Jones enlisted in the 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, organized at Harrisburg in August 1862. During his time with the regiment, Jones saw combat at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He was part of the assault by Union troops under General Humphreys on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg.

In the spring of 1863, having been promoted to corporal, Jones was wounded just before the main action at Chancellorsville while his unit was crossing the Rapidan River. He insisted on remaining with the regiment for the battle.

Jones returned to work at the Cambria Iron Company after his regiment mustered out in late May 1863, but he did not remain out of the war. He organized a company of infantry volunteers and was mustered in as captain on July 20, 1864, serving honorably until June 1865.

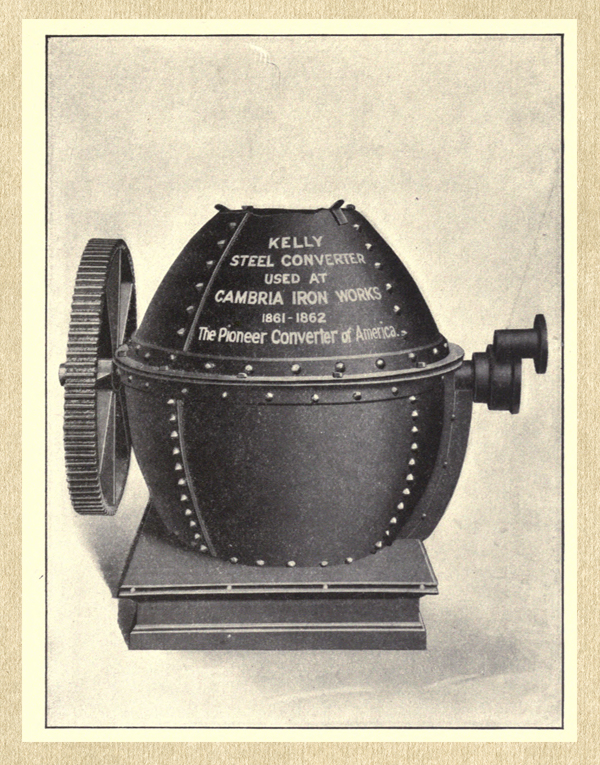

The Cambria Iron Company to which Bill Jones returned after the war had become one of a handful of American companies at the leading edge of iron and steel technology. While Jones had been serving as a soldier, his employer had been experimenting with the Kelly converter, brainchild of Pittsburgh-born metallurgist and inventor William Kelly, who had independently developed a pneumatic steel production method similar to the Bessemer process.

Thus did Bill Jones, able machinist and combat veteran, land in the proving ground for one of the great industrial breakthroughs of the century. In 1872, the Cambria Iron Company became the sixth Bessemer steel plant in the nation with the installation of Bessemer furnaces designed by engineer Alexander L. Holley.

That same year, Jones was promoted to assistant superintendent, aid to George Fritz, general superintendent of the Cambria Iron Company.

Cambria Iron Company c. 1860. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Cambria Iron Company c. 1860. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Kelly Converter.

Kelly Converter.

Edgar Thomson Steel Works

In Pittsburgh, Andrew Carnegie was making plans to build the first Bessemer-process steel mill in Allegheny County. With railroads expanding lines across the country, the demand for steel rails was soaring, and Carnegie saw a business opportunity. Carnegie and his brother, Thomas, formed a partnership with several other men. They purchased nearly 107 acres of riverfront property in Braddock.

The goal was to build a state-of-the-art steel works, so Carnegie hired Alexander Holley to design the new mill and Bill Jones to run it. Holley was receptive to input from Jones, whose experience at the Holley-designed Cambria Iron Company proved invaluable.

The other critical component, of knowledgeable men to run the advanced machinery, was resolved when a number of steelworkers loyal to Bill Jones followed him from Johnstown to Pittsburgh. Without an explicit plan for it, a talent raid on a key competitor effectively took place, with the newly formed Edgar Thomson Steel Works gaining the advantage.

With the frequently downward shift in the price of steel rails, the challenge for E.T., as Edgar Thomson Steel Works was often called, was to use innovation and efficiency to remain profitable. Under Jones’ superintendency, E.T. thrived, with steadily growing output and profits.

Jones’ capable work quickly made an impression upon Andrew Carnegie. The two men were strangers when Jones came over from the Cambria Iron Company. In his autobiography, Carnegie described Jones as “young, spare and active, bearing traces of his Welsh descent even in his stature, for he was quite short. … We soon saw that he was a character. Every movement told it.” Carnegie credited much of the success of Edgar Thomson Steel Works to Captain Jones.

In later years, Carnegie offered Jones a partnership in the firm, but Jones turned him down. He had his hands full running the works and did not want to be distracted by corporate business concerns. Jones’ counter to Carnegie’s offer was that he be paid a really big salary, “if you think I’m worth it.” Carnegie proceeded to pay Jones the same salary as the president of the United States.

What Jones brought to his leadership style was a keen concern for the human factor. Physically fearless, he did not hesitate to step in and work beside his crews on any job. Having earned their respect, he captured their devotion by demonstrating fair-mindedness, modesty and an awareness of the grueling labor involved in steel-making. Jones favored an eight-hour workday, which he implemented for a time at E.T. in the mid-1880s, but the arrangement proved unsustainable in that era with the pressures of falling rail prices and ruthless competition.

Jones was also a familiar member of the Braddock community, frequently seen by and among the men who worked for him. Snacking on bags of peanuts, he was a fixture at baseball games, horse races, parish festivals and concerts. He gave liberally to the needy and was the patron of many fundraisers. Jones’ house was on Township Road, between Kirkpatrick and North Streets. Township Avenue was renamed Jones Avenue in the early 1890s, after Jones’ death.

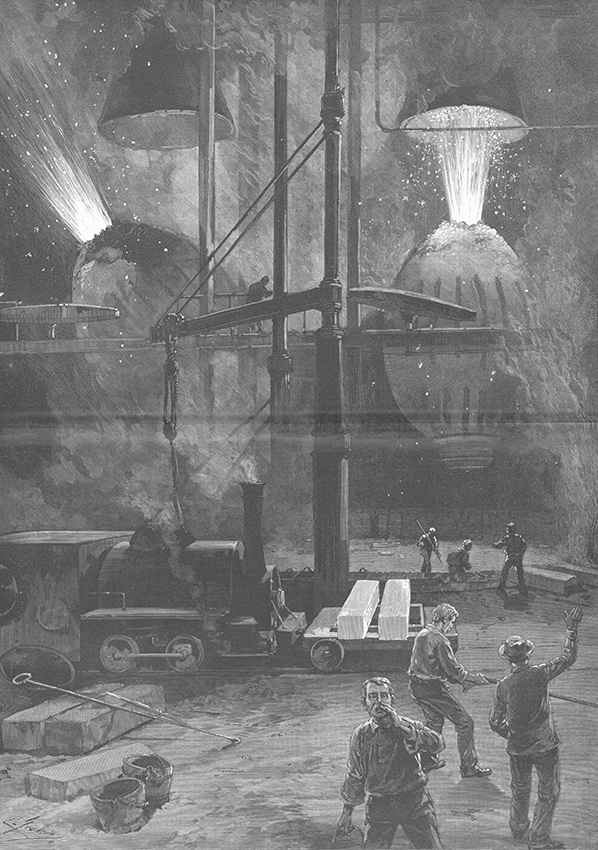

Making Bessemer steel in Pittsburgh. Illustration by Charles Graham. Harper's Weekly, April 10, 1886.

Making Bessemer steel in Pittsburgh. Illustration by Charles Graham. Harper's Weekly, April 10, 1886.

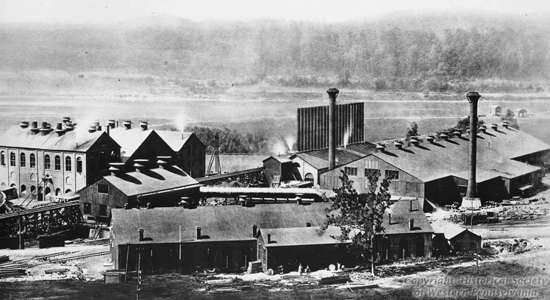

Edgar Thomson Steel Works in 1875. Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Edgar Thomson Steel Works in 1875. Courtesy of Senator John Heinz History Center.

Innovator

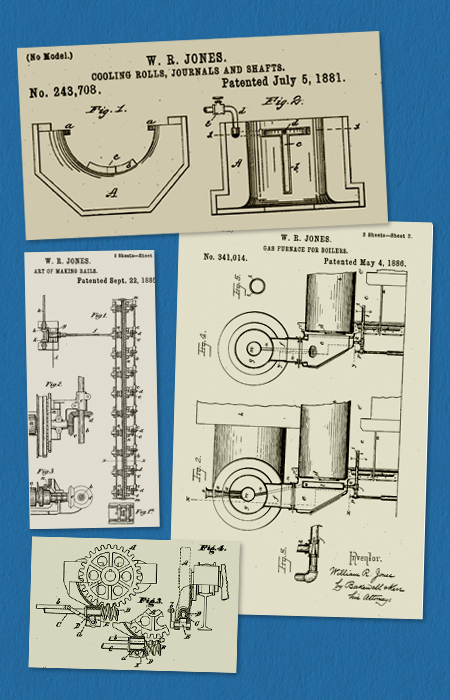

Whenever a device was needed to improve steel production, Bill Jones’ mechanical mind went to work on a solution. He was issued more than a dozen patents during his years at Edgar Thomson Steel Works.

He invented an ingot compressor, a method for symmetric flattening of the heads of railroad rails, a device for operating ladles in Bessemer steel-making, improvements in gas furnaces for boilers, and many other practical improvements to production and efficiency.

Edgar Thomson Steel Works formally opened in September 1875 with about eight hundred hands. From the start, the mill was a success, making a profit in its very first month.

By 1889, the works had expanded its footprint with additional acreage, and about 8,000 were employed there. Bill Jones was at the forefront of making the United States a world leader in Bessemer steel production.

Pittsburgh photographer and Dollar Bank customer Ernest Histed took this photo of Johnstown in June 1889. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Pittsburgh photographer and Dollar Bank customer Ernest Histed took this photo of Johnstown in June 1889. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Johnstown Relief

Pittsburghers were among the first to respond to the disastrous flood of May 31, 1889 at Johnstown, Pennsylvania, not just because of the physical proximity of the two communities, but also because many citizens had ties to both towns. This was true of Bill Jones, who had lived and worked in Johnstown for over a decade before he moved to Pittsburgh.

The flood had jammed the devastated streets of Johnstown with immense wreckage. There were limited options on how to clear the tightly packed sand, mud and debris. Bill Jones and 300 men from Braddock, bearing picks, shovels and axes, went to Johnstown in two deployments on the third and fourth days. Jones paid out of his own pocket for the expenses of his relief corps.

The situation was desperate not just for the traumatized survivors but also for relief workers. Filth, disease and exposure to the elements were formidable challenges. Incidents of lawbreaking in the wake of the disaster threatened to undo what little order was being restored, yard by yard, street by street.

To Jones’ credit, he came to the defense of Hungarian immigrants in the town who had been wrongly accused of looting. He noted that his own relief corps from Pittsburgh consisted of many Hungarians whose faithful and diligent character made them excellent workers.

Jones’ humanitarian work at Johnstown was the last great gesture of a remarkable life about to be cut short.

Furnace C

Bill Jones had overseen the construction of seven furnaces at Edgar Thomson Steel Works. The furnaces bore letters for names, A through G. Furnace C, after malfunctioning for several days, became completely blocked by Thursday, September 26, 1889. The tap and cinder holes were clogged.

Around 7 P.M., Bill Jones was directing the men in tapping a hole at the base of the furnace (to allow the molten metal to flow out) when the top gave way with blast of superheated gases and a stream of white-hot metal.

Jones was hurled backward into a gap between two Modoc cars, striking his head on one of them. A Hungarian steelworker named Andrew Kallony (spelling varies in the newspaper reports of the time) was incinerated on the spot, and several other men besides Bill Jones suffered injuries.

Unconscious and severely burned, Jones was taken to the Homeopathic Hospital. The other injured steelworkers were rushed to Mercy Hospital. One of these, foreman Michael Quinn, age 28 and a married father of three, died of his injuries.

Newspaper accounts reported that Jones’ condition was improving, but he succumbed the evening of September 28th without having regained consciousness.

The unexpected death of Captain Bill Jones was a great shock to the Braddock community and the steel industry, where Jones’ accomplishments were widely recognized. Five thousand men from Edgar Thomson Steel Works marched in his funeral parade, which was also filled with Grand Army of the Republic veterans and thousands of other steelworkers from around Pittsburgh. The tributes poured in.

Decades after Jones’ death, the Pittsburgh Press noted that one of the proudest claims a retired Pittsburgh steelworker could make was to be able to say that he had worked with Bill Jones.

Captain Bill Jones' contributions to Pittsburgh steel were recounted in a 1933 series on the industry. A newspaper illustrator depicted the accident that fatally injured Jones. Courtesy of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Archives.

Captain Bill Jones' contributions to Pittsburgh steel were recounted in a 1933 series on the industry. A newspaper illustrator depicted the accident that fatally injured Jones. Courtesy of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Archives.

Welshman

Bill Jones was a member of the St. David’s Benevolent Society, a Welsh fraternal organization. Proud of his Welsh heritage and the literature and music of Welsh culture, he supported local Eisteddfod celebrations as judge, speaker, and patron of prizes.

In the late 1800s, Pennsylvania and Ohio were home to the largest population in the U.S. of Welsh immigrants and their descendants. Small neighborhood celebrations went city-wide in the city of steel with the first annual Pittsburgh Eisteddfod in 1883. In an evergreen-bedecked Lafayette Hall on Christmas Day, Welsh language and music rang out, and Bill Jones awarded cash prizes to glee clubs from Pittsburgh and Youngstown.

In 1913, the Pittsburgh Eisteddfod Association celebrated the William R. Jones Memorial International Eisteddfod.

Captain Jones was a member of the Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the American Institute of Mining Engineers, and the Iron and Steel Institute of Great Britain. He served as Senior Vice Department Commander of the Pennsylvania G.A.R. from 1888-1889.

Bill Jones’ wife was the former Harriet Lloyd, who was born in England and whom he married in Tennessee in April 1861. The couple had four children, two of whom survived to adulthood. Harriet Lloyd Jones died in 1896.

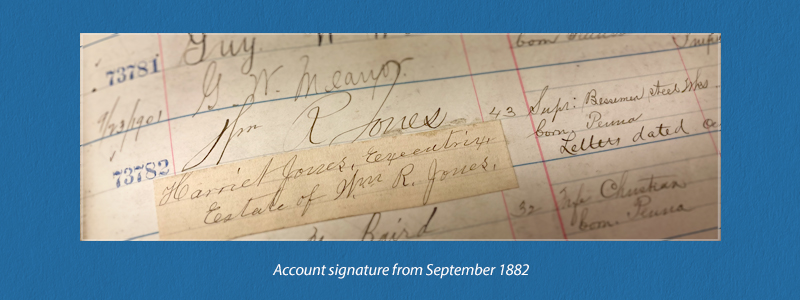

Captain Jones opened a savings account at Dollar Bank in September 1882. He signed his name “Wm. R. Jones."