Fourth Avenue Building and Lions

Can't visit the Dollar Bank Fourth Avenue Building in person?

You can still view the majestic architecture and grand interior of the oldest surviving bank building in Pittsburgh's historic financial district.

Dollar Bank's Fourth Avenue Building: An Architectural History

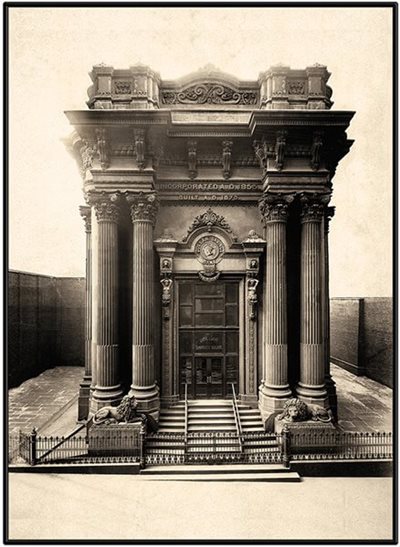

Dollar Bank's Fourth Avenue Building, c. 1880s. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

In its first decade, Dollar Bank experienced tremendous growth. By the end of the Civil War, the Bank was opening an average of 100 savings accounts weekly and handling more than $70,000 in transactions each week. The Bank's rented rooms at No. 65 Fourth Avenue had become inadequate to accommodate the growth in daily operations.

With approval from the Board of Trustees, in April 1865 the Bank purchased several lots on Fourth Avenue between Wood and Smithfield Streets. On those lots were the law offices of attorneys George S. Selden (122 Fourth Avenue) and Andrew W. Loomis (124 Fourth Avenue). Attorney A. Kirk Lewis (120 Fourth Avenue) had died in 1860, but the property was still held by his estate. The Bank paid $12,000 total for the lots, thus acquiring sixty feet of frontage on Fourth Avenue. The lots were deep, extending 85 feet to Third Avenue.

Due to a shortage of building materials after the Civil War, the bank building project progressed slowly. It took another four years before construction began, in March 1869.

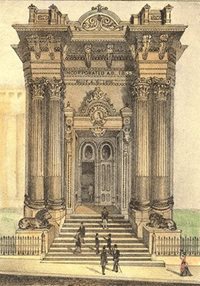

Architect Isaac H. Hobbs & Son of Philadelphia was selected to design Dollar Bank's new building. A specialist in residential architecture, Hobbs frequently published ornate house designs in the popular Godey's Lady's Book, a monthly home and fashion guide for women. A sketch and floor plan for Dollar Bank's Fourth Avenue Building appeared in the February 1870 edition of Godey's.

Dollar Bank's cash books record a flurry of telegrams in April and May 1869 between the Bank and Hobbs' firm in Philadelphia. The architect sent plans and stone samples to Pittsburgh for approval. The Bank put ads in the local papers requesting bids on the various construction contracts. The firms of William C. McCarthy and Felix Rodgers excavated the cess pool and cellar, while Pittsburgh contractor and stone mason John L.L. Knox was put in charge of setting and dressing the stone. Responsible for getting this material quarried and shipped to Pittsburgh was stoneyard owner William Gray of Philadelphia.

The amount of stone Hobbs planned for the new building was massive. Fourteen thousand tons of brownstone quarried in Portland, Connecticut, would comprise the facade. This was to be supported by columns of Allegheny Stone in the basement. As vast quantities of stone and other building materials accumulated, quite literally, in the street, the stretch of Fourth Avenue between Wood and Smithfield underwent significant alterations to accommodate the construction. In September 1869, pavement in front of Mayor Jared Brush's office, across the street from the Bank's building site, was taken up, and streetcar track was moved to the north side of Fourth Avenue, at a cost of $150 to the Bank.

The Bank hired many local businesses for jobs on the building: civil engineer Francis Owens; plumbers Jarvis, Halprin & Co.; foundry work from Marshall Bros. and William J. Anderson & Co.; William Boyd & Son for bricklaying and carpentry; iron manufacturers Moorhead & Co. and William B. Scaife; George Howarth for stone work on the vault; plasterers William Pascoe & Co.

The project cost $190,000, and, when finished, the grand Beaux Arts structure set the standard for all subsequent banks constructed along Fourth Avenue, the heart of Pittsburgh's financial sector. The building's lavish design and use of imported New England stone were expressions of robust confidence, marking the emergence of Pittsburgh as an industrial and financial heavyweight on the American scene.

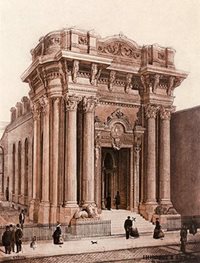

Hobbs' architectural plan spared no detail. The building was constructed using 14,000 tons of brownstone quarried in Portland, Connecticut, pink Quincy (Massachusetts) granite, and copious amounts of marble and brass. William Gray of Philadelphia executed the stonework on the façade. Flanking the entrance were two lions, each sculpted on site from a single, massive block of quarry-bedded Portland brownstone. The artisans who carved the lions were Max Kohler and his assistant, R.C. Morgan.

Left: Architect Isaac Hobbs' rendering. Right: An 1876 pen and ink sketch.

Recurring motifs of dollar coins and lions were repeated in sculptures and carvings throughout the building. A marble teller counter, marble floor and elaborate chandelier in the main banking hall, where the ceiling rose a dizzying thirty feet, welcomed the Bank's depositors. A reporter from the local Daily Gazette was duly impressed, noting in an April 1871 article: "The noble structure [is] surpassed in permanence, symmetry and beauty by no public edifice in any American city."

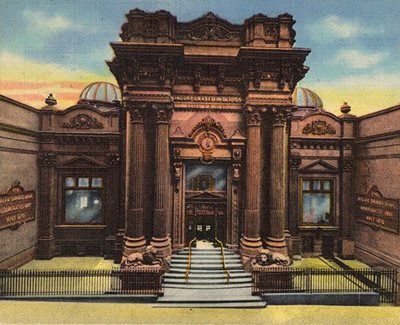

Over the next several decades, as Dollar Bank's depositor base grew, the Fourth Avenue Building was expanded to accommodate the increased volume in daily operations. In 1896, executive offices and a new board room were built at the rear of the building, and floor space was opened up for additional customer service. In 1905, two wings were added, using extremely durable East Longmeadow stone, quarried in Massachusetts. The architect for this expansion was a Pittsburgher, James T. Steen, a Dollar Bank depositor since 1868.

Today, our Fourth Avenue Building is the oldest surviving bank structure on Fourth Avenue. It has been continuously owned and operated by Dollar Bank since its inception. The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Local experts in historical architecture, such as James D. Van Trump, Walter C. Kidney and Franklin Toker, have noted the significance of Dollar Bank's Fourth Avenue office in their publications. Dollar Bank's lions, symbolizing, in the words of Bank historian William T. Schoyer, "guardianship of the people's money," have become some of the best-known and highly regarded pieces of sculpture in Pittsburgh's downtown.

As a beloved Pittsburgh landmark, the building and its lions have captured the imaginations of many local artists. Current-day customers who ascend the steps past the lions are treading the same steps as those depositors who came to marvel at the majestic new building in April 1871. Architect Isaac Hobbs' vision, to create a structure that would stand for generations and serve the people of Pittsburgh, has been magnificently realized.